You might not be able to tell from his affable way and easy smile, but Rick DeCristofaro might have one of the toughest jobs in America at the moment – he’s a college president. DeCristofaro, 72, heads Quincy College. His pressures have nothing to do with student protests over Gaza. There are no encampments outside the school’s Cordage Park campus. He’s reckoning with a different kind of crisis, one that could radically remake the nation’s higher education system. Increasingly, parents and students are asking: Is a degree worth being saddled with a decade or more of loan payments plus interest? The answer is often: Absolutely not.

Student debt tops $1.7 trillion (yes, trillion), some colleges’ sticker prices are nearing $100,000 a year, and small private schools are shutting down because of declining enrollment.

There is little doubt that seismic changes are ahead.

Here in Plymouth, Quincy College has long positioned itself as a lower-cost alternative to universities with lush grounds, dorms outfitted like high-end hotels, and food services that cater to specialized diets. You won’t find any luxury amenities at the school’s Cordage location, or at its main campus in Quincy. It’s a no-frills educational experience, with a student population that skews to the older side. Fifty-five percent of the school’s Plymouth students are ages 19 to 25, and 23 percent are between the ages of 26 and 35. Total enrollment is about 2,750, including 300 students in Plymouth. Nearly half of them receive some type of financial aid, which includes grants and loans. Many have full-time jobs and families. Most are seeking skills that will allow them to make a good living.

Quincy College is public, but receives no funding from the City of Quincy, making it heavily reliant on tuition and fees. It only offers three bachelor’s degree programs – in computer science, business management, and psychology. Its focus is on two-year associate degrees (there are 35 programs), and certificate programs (there are 21) in hot areas such as nursing, health sciences, and physical therapy assistants. Compared with many state schools and any private one, it’s a relative bargain. For example, it costs about $19,500 for an associate’s degree and $40,000 for a bachelor’s diploma.

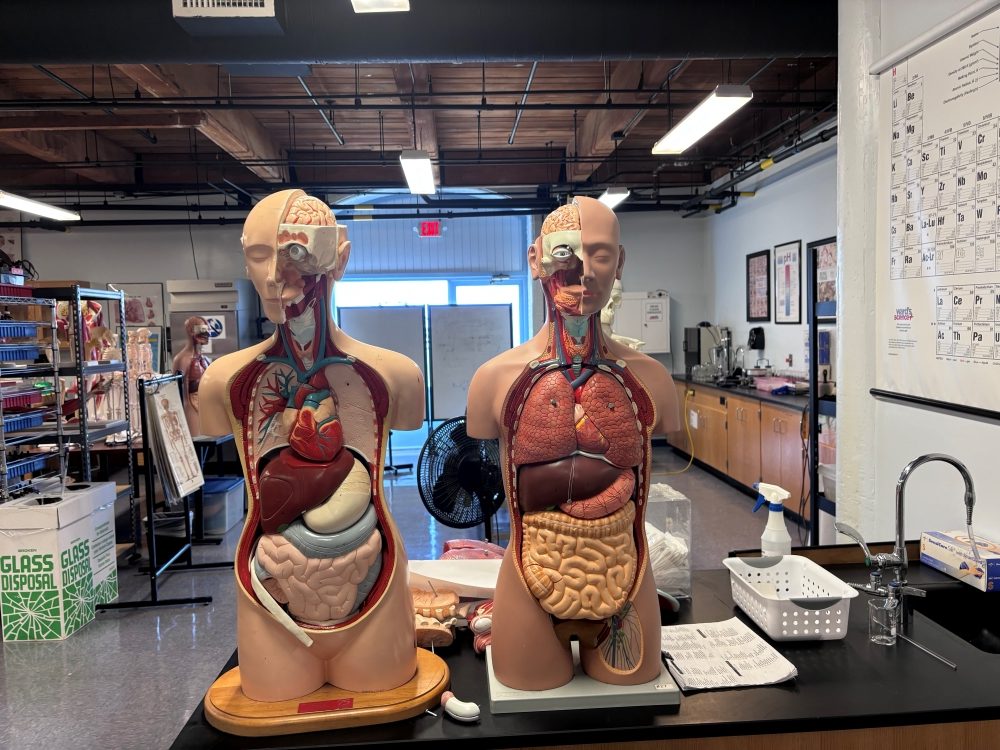

The school has offered classes in Plymouth since 1991. Today, it occupies about 40,000 square feet in the former rope factory complex. On a recent tour, the space was quiet because most in-person classes are held in the morning. In one brightly lit room, nursing students nearing the end of their program crowded around a dummy “patient” who had suffered a stroke. In a nearby classroom, students took in a lecture.

DeCristofaro became president in 2020, not long after after the Covid pandemic put a hold on in-person learning. It added another layer of stress to his position. He came to Quincy College after decades in that city’s public school system, including 19 as superintendent. There’s even a school named in his honor.

For years, Quincy mayors appointed politically connected types to run the public college, with mixed results at best. DeCristofaro’s credibility as a veteran academic administrator was a major change. And he’d need every bit of that deep experience to turn things around. In 2018, Quincy College suffered a major blow when the state Board of Registration in Nursing withdrew its accreditation of the school’s nursing programs after determining they were seriously flawed. Hundreds of students were left in the lurch, and the school’s reputation took a hit. The president at the time, former city clerk Peter Tsaffaras, was forced to resign, and Quincy Mayor Tom Koch temporarily ran the college.

Today, the nursing programs have been reinstated, but the rebuilding and reconfiguring continues. In a wide-ranging conversation, DeCristofaro talked about his life in education, his vision for keeping Quincy College relevant, and the importance of its place in Plymouth.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

You worked decades as an educator before coming to Quincy College.

Yes, being in Quincy for a very long time, I knew the college, I knew its progress, and the issues along the way. I started as an elementary school teacher, taught education in middle school and high school, and then became part of the Quincy Public Schools administration as an assistant principal, assistant superintendent, and superintendent for just about 20 years. I knew at that point that there were some issues with consistency at the college and so I applied [to become president] in March of 2000.

Great timing.

Right in the middle of the pandemic. And leaving the school system at the time, I felt a little guilty.

How many superintendents become college presidents?

It was kind of a unique transition. But I had an idea of what the vision could be and it really made a lot of sense to me.

Were you recruited to the job because the school was in trouble?

No, I just wasn’t ready to retire. I had been in the school system since ’75. I just knew there were some issues [at Quincy College] that maybe I could help with. That was really my incentive – to try like heck to leave it far better than I found it. But of course, then you’re starting when the entire world is in a crisis.

What was that like?

Very difficult. We had shut down the [Quincy public] schools. We had started to supply families with technology the best we could and work on online courses. When I came to the college in June 2020, it was pretty much a ghost town. But it gave me time to talk to the college administrators about where they were right then and where we needed to be. That’s when we started our strategic plan.

What’s the primary role of a school like Quincy College?

Many of the students that come here are ready to succeed. They feel that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel. And if they don’t, that’s our job to make sure that they have opportunities. That’s really what it’s all about. A lot of it is personalized education and you don’t get that at a large community college. You don’t get that, certainly, at a state university. Our students need to know that they can talk with someone, that they can trust someone, that they’re valued. The instructors, the professors, they have to work extra hard in order to make them understand that we’re available for you. Students who come here are high school graduates, many of whom are thinking, “Well, that’s it for me. That’s as far as I’m going in education.” They’re not sure college is for them. They’re certainly they’re not applying to BU or Northeastern.

I imagine you have to be nurturers, to give them the confidence that they can do it.

You’re absolutely correct, and that’s what we do best. Our goal – whether you’re in Plymouth or Quincy – is that you really feel like you’re part of the school community.

Higher ed is reaching an inflection point. Enrollment at a lot of schools is plummeting. People are saying, “A college education isn’t worth the price any more.”

The enrollment cliff is what we’re talking about. People have known that a long time, that enrollment was going to drop everywhere. [To counter that] we’ve worked on a couple of things. We’ve worked on early-college high school classes. We now have about 260 high school students participating. Students can take these accelerated courses in high school and get college credits. They can go to Quincy College, which we want them to do, but at least 80 colleges accept the credits. Many of our early college students are low income, first generation, students of color. This is a gateway for them.

What’s the biggest deficiency in high school education that needs to be fixed so kids can succeed in college? I get the sense that it has a lot to do with writing.

I think that started a while ago with students not really being able to write a check, not being able to write cursive. Not that that’s huge, but it’s a discipline that is missing. Going back to my superintendent days, I made sure that those elementary and early middle school classrooms had a writing component. Ultimately, you want success for these students. That means when they go out looking for a job that they’re ready, that they can express themselves in writing.

I can do that, fortunately, but my handwriting is horrible.

Students print, they don’t use cursive. Or when they do, they write their signature and you can’t read it, which I can’t stand.

People say to me, “Oh, my God, I can read your writing!” And I say, “Well, I taught fourth grade at one time.”

We have programs for English as a second language. We have programs like pharmacy tech and biotech that are doing very well. These students go from the classroom right into jobs. The biotech firms from Cambridge are constantly visiting our classrooms.

You no longer need to have a four-year degree to work in biotech.

Yes, we have a two-year biotech program. We also have a certificate program. Sometimes people look at the two-year program and go, “Why?” Because you can get hired right now. Biotech firms want a two-year [education] commitment. They tell our students. “I’ll hire you after one year, but I want you to finish that second year and think about the courses that you take and the growth that you can have in our company.”

Next, we’re looking at where we go with health sciences. Do we look at an MRI program, a dental hygienist program? Some of these are occupations that students just need a certificate for.

We’ve also got three baccalaureate programs now. We have a four-year psychology degree, a four-year computer science degree, and a four-year business management degree. We’re trying to create these pathways for any student that comes in to say, look, this is where you can go. You don’t have to go anywhere else. You don’t have to go to a community college. You don’t have to go to a state university. We’re going to take care of you right here. And we just got full program approval for our nurses.

Losing that program’s accreditation six years ago threatened the school’s existence. (At the time, the state cited poor NCLEX scores – which measure nursing students’ learning – the school’s subpar curriculum, and a high turnover rate in leadership.)

There were close to 500 nurses in the program. It was a huge blow – almost $10 million. We’re now back to a point that it’s got full approval by the Board of Registration in Nurses.

Can you talk more about the so-called enrollment cliff?

Most people define that as the birth rate’s declining so fewer people are going to college. But we’re looking at a different market. It’s not just people coming out of high school. It is people in their 20s, their 30s, or in some cases, older. It’s people who’ve had job loss or unexpected family issues. Those people are now looking at college and we want those students, those people who aren’t “traditional” students. You can deal with the enrollment cliff if you’re looking for college students in non-traditional places. We are.

But keeping prices reasonable is still a struggle. You can’t afford to have enrollment drop.

We have to be really careful. Our financial aid group is tremendous. A lot of kids don’t bother with [filling out] the FAFSA form, so we’re calling them in, we’re constantly communicating, making sure they do that. We do a ton of outreach to our students. Our costs are obviously much lower in so many ways, but it’s still difficult for them. We have to keep our tuition as low as we possibly can. We don’t get a lot of state support. In fact, we get very little. Everything we get is tuition and revenue grants. Without the enrollment that we need to get the tuition that we need to drive and operate, we would be in real trouble. We’re different than other schools in we’re not relying on anyone but ourselves, in a sense. Everyone knows the mission. Everyone understands that it never stops. Because that’s what going to keep us in a place where we can have students that can afford to come here and not feel so much debt when they leave.

A student isn’t going to take on $200,000 in loans going to Quincy College. Nonetheless, doesn’t the school have a responsibility to make applicants aware of what they’re signing up for when they borrow?

It’s critical because I think they forget the fact that they need to pay somewhere along the line. We have constant reminders that go out about their balance. It’s effective but not always as effective as it should be. We have a great partnership with TD Bank [through which] they come in and talk about finances with our students.

They talk about how to make it through college and beyond without significant debt.

Is it possible for most students to cash flow school these days?

There are students that do that. Many of them have parental backup, or their grandmother or grandfather help out. Many know they’re going to need that second job [to cash flow tuition].

Could we go too far in the direction of college only being about how much money you can earn when you get out? Are we at risk of losing the aspect of education that is about overall enrichment and exposure to new ideas?

The setup here is unique. The students are unique. But we have as many activities as we possibly can to try to balance things out, including here in Plymouth. Quincy College is a great culture for certain students. They know when they come here that they’re not going to have all the extras. But we try very hard – whether it’s cookouts, coffees, breakfast in the student lounge. I think we need to do more, like to build on community service, because that helps with the balance. Who you are is far more important than anything else in life. So that service piece, to me, is absolutely critical to make sure these students know how to give back.

The programs that we have, like radiology, they’re critical for students and for the college. Students need to have a return on investment and also be very valuable in the workforce. We’re lucky in a way that we are small. We can adapt and try things. If they fail, we can try something else. Large universities don’t have that because there are a lot of barriers built into higher education – professors that say, “This is what I teach.” Everyone’s got their silo. We have some of that, but we try very hard not to. We train across disciplines. We build teams of people. Even the English majors are talking to the biotech majors, just to get more ideas and keep fresh.

If you’re smaller and leaner, closer to the ground, you can make these changes.

But ultimately it comes down to finances.

If the economics don’t work, you can’t offer bachelor’s degrees. There’s the threading the needle aspect of how to get the most value out of what you’re trying to deliver. It’s responding to what your student population and your employer population in the region wants.

A main role of a college president is fundraising. How much of your job involves that?

Well, coming from K-12, I didn’t have go out there and beat the bushes.

But you had to go before a school committee and talk money.

Oh, yes, many school committees. What we’ve done is to create the Quincy College Foundation, to create an endowment. We want to focus on student scholarships in all our programs. And that brings stability, of course, and they really haven’t had it here. What I’m looking to do is to create a board of trustees. I would be head of the trustees in a way, as the president, but eventually they’d get some someone who has a couple more dollars than I do and more time to build that foundation that’s needed. We don’t have a lot of people that have graduated that have made it big and can give us millions. What we do have is a lot of people that love Quincy College. We need to do outreach to them, to say to our alumni, “Look at what the school did for you.” Give back to the college, whether you make $50,000 or $250,000.”

You have to spend some of your time courting people that have some money to give. There are people that have money and will give it to the college, but they also kind of say, “What’s in it for me?” They want to know what’s going on at the college.

They want their name on something.

Yeah, that’s really the ultimate. That’s what colleges can do, name a hall after someone. But even just like, “Show me where my money is going.”

Which is reasonable.

It’s very reasonable, and I think that’s what we owe people. It’s stewardship, making sure that these people give again, that they understand what their gifts are used for.

There’s a lot of tension on campuses. Obviously, it’s different here, but is there any kind of discussion taking place?

We’re not immune to it. Our professors listen to a lot of opinions. Many times, it’s like the United Nations in our classes. So, not only do you have to be careful as a professor [in] what you say, you also have to be careful as a college. As a college president – and this may not be the right answer – it’s just about not saying something that you will regret. I know it sounds kind of cowardly.

Is that self-censoring or inhibiting free speech?

No, but it’s probably different when people are living on a campus, and they have so much time together. Our students, most of them, they’re somewhat transient as opposed to other colleges.

What about the diversity of the school population. Plymouth is a mostly white town, while Quincy is not.

Overall, 58 percent of our students who share [racial and ethnicity information] are students of color. Obviously, that’s much higher than an Ivy League school. And I would say it’s much higher than most community colleges.

Is that by design or it just happened?

It’s always kind of been that way. We have students from Boston that come in, whether it’s Hyde Park or Dorchester. They take the Red Line to Quincy. We’re seven to eight percent Asian. Quincy has a pretty big Asian community. We’re probably about 26 percent Black. The Plymouth campus primarily is a white population. I’ll give you one piece of information I have on the Plymouth student population: 46 percent are on financial aid. This a beautiful place. It’s a great town. It attracts retirees and it also attracts young families. It’s about finding a balance. When it’s neither one of those things, that’s where the challenge comes in.

What’s changing about the role of the college in Plymouth?

We need to adapt to the market. And the market is, again, about workforce development, making sure there’s a connection with the community, making sure we have internships. Because I think the enrollment here is going to stay kind of where it is. It’s up a bit. But it’s not what it was, say, 15 years ago. I don’t want to say it’s because of Covid. I don’t use that as an excuse. I say, let’s go forward. But I think it’s more difficult because the enrollment at both Plymouth North and Plymouth South high schools isn’t what it was back then, as well.

We need to market the college more. I’ve met with the superintendent, the assistant superintendent, a few times to talk about dual enrollment, about early college. We give a scholarship to Plymouth North and Plymouth South students to come here for the first semester free. So we’re doing those things. But we need to be understanding of the changes Plymouth is going through and adapt in order to get students to come here.

Do you find Plymouth’s high schools and students receptive, or is there a stigma about the local college – that coming here means you’re not reaching high enough?

You know what? It’s the same in Quincy. You graduate from Quincy high school and, boy, you’re going to go to Quincy College? My mother and father can’t talk about that at the next cocktail party. But the kid’s got a job, an education, and doesn’t owe a lot of money. They can talk about that.

Mark Pothier can be reached at mark@plymouthindependent.org.