With the current effort to draw attention to one of Plymouth’s overlooked Revolutionary heroes – Mercy Otis Warren – perhaps it’s also time to highlight the home she and her husband shared in our town.

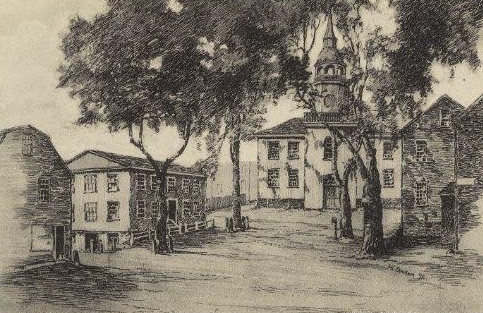

Otis Warren, a friend of Abigail Adams and author of the first full account of the American Revolution, lived at the corner of Main and North streets in the two-story brown building that is currently home to businesses including Edge Pizza, the law offices of Moody and Knoth, and La Vie Luna Apothecary. It is a house with not only a remarkable history but also one that stands as an outstanding example of a rare architectural style: a two-story colonial era building with a gambrel roof.

First the pedigree, which comes directly from the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS) maintained by the Massachusetts Historical Society.

“The strip of land along Main Street between North and Middle streets was first owned by Nathaniel Morton, Secretary of Plymouth Colony and Gov. Bradford’s nephew, who sold the entire lot in 1675 to John Wood. By 1705 the lot came under the ownership of Thomas Little and remained intact until his death when the large lot was subdivided by his heirs starting in 1726

(Davis, pp. 178, 189). This lot was sold to General John Winslow in 1726 who had the house built. Gen. Winslow was known for his service in the Cuban expedition of 1740 and for his part in the removal of Acadians from Nova Scotia in 1755. He was considered one of the “most distinguished” military leaders of New England during this time (Davis, P. 178).

In 1737 Gen. Winslow sold it to James Warren and it became known as the Warren Lot, which included a portion of North Street.

Mrs. Mercy Otis Warren wrote a history of the American Revolution and “carried on correspondence with John Adams” while she lived here (Davis, p. 178). The Warren Lot remained intact in the Warren family until 1832 when it was sold to Nathaniel Russell.”

Now to the house’s distinguishing feature: A gambrel roof is a sloped roof with two surfaces of different angles on each side of the main ridge beam. In the United States, they are also called Dutch roofs. The origins and history are lost to time but the gambrel roof that is common in North America is thought to have originated here rather than in Europe.

While often seen on simple Cape Cod style homes, the two-story version is a much rarer animal. There are pockets in New England where this building feature can be seen, as well as in the greater Philadelphia area and Tidewater Virginia. Apart from Plymouth, other New England examples can be found nearby in Kingston and, farther afield, in pockets from Newport, R.I. to Salem, Boston, Deerfield and its surrounding communities of the Connecticut River Valley.

So why did certain areas end up with such distinguished roofs? Well, follow the money.

First, building such a house required a housewright. The housewright was a term used to describe an early home builder and carpenter. When the two-story gambrel began to appear, it wasn’t something that could be constructed without professional help. Like today, hiring a housewright was not an inexpensive option.

Moreover, the gambrel roofed timber frame structure was not an easy build. It required a timber framer with experience and finesse. I often use the example of preparing eggs for breakfast to framing a gambrel roof. Almost everyone can prepare scrambled eggs; the same would apply to a carpenter erecting a simple gable roof. The gambrel roof, however, is like preparing Eggs Benedict. It requires more than a simple knowledge of cooking, it requires additional time and materials, and most importantly, it’s more expensive. In the end, the homeowner of the colonial era with the gambrel roof was hiring the best builder and had money to spend.

So, it’s no surprise that gambrel-roofed houses were located in wealthier colonial towns. In its heyday, Plymouth builders were putting up some of the best and fanciest stock around. Sadly, our shallow harbor would soon become the town’s economic downfall and the money moved to deeper ports like Salem, Newburyport, and Boston. Styles also changed, and like fashion, the gambrel fell from grace.

Plymouth currently has four remaining examples of these homes. The 1726 Winslow-Warren House at 65 Main Street where Mercy Otis Warren lived leads the parade, to be followed by the 1734 Leonard House at 21 Leyden St., the 1750 May House at 32 Middle St., and the 1794 Tribble House at 33 Leyden St.

Others that existed in our downtown core have been lost. They include the 1679 Leach House that stood at the corner of Summer and Spring streets, the 1698 Shurtleff House at the corner of Market Street and Town Square, and the Bradford House (unknown date) at the corner of Main Street and Town Square. There were also two on Court Street, the Dyer House (circa 1750) and a home once at 4 Court St. with an unknown date. An additional home is shown on the 1882 bird’s eye view map on Middle Street where a municipal parking lot is now located.

The Kingston homes are the 1714 Little’s Tavern at 191 Main St. and the Sever House at 2 Linden from 1755 that was originally built with a gambrel roof until a massive stylistic remodel changed it in 1800.

The time span from the earliest two-story gambrel home in 1697 to the latest in 1794 is less than 100 years. Think about it: It is entirely possible that these homes in our area could have been constructed by a sole housewright and his son over the course of less than a century. But whether it was a sole family of housewrights, or a group of them, it’s a legacy left in Plymouth that endures more than 300 years later. We are lucky to have them.

Bill Fornaciari, a lifelong resident of Plymouth, is the owner of BF Architects in Plymouth. His firm specializes in residential work and historic preservation. Have a comment, question, or idea for this column? Email Bill at billfornaciari@gmail.com.