After graduating in 1986 with an architectural degree from Roger Williams University, my fellow graduates and I were ready to change the world. My classmates spread out across the country, landing jobs in places like New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Seattle, and San Francisco. I returned home to Plymouth.

A major building boom was underway in the United States, giving rise to what became known as the “Starchitect,” architects “whose celebrity and critical acclaim,” according to Wikipedia, “have transformed them into idols of the architecture world and may even have given them some degree of fame among the general public.” As it turned out, it was a relatively short-lived phenomenon, but I knew that many of my fellow classmates were working in places where stupendous projects by the likes of Robert A.M. Stern, Frank Geary, I.M. Pei and Michael Graves were under construction.

This gave me pause: Had I made a good decision to move home? Would I have a decent career in a small town? Do we have any buildings by famous architects in Plymouth? The answer to all these questions was yes and I would like to invite you to consider some buildings designed in Plymouth by “Starchitects” of different eras, including our own.

The first Starchitect to have worked in Plymouth was Charles Bulfinch, who lived from 1763 to 1844 and is best known for designing the U.S. Capitol Rotunda and Dome, as well as our own Massachusetts State House.

In Plymouth, Bulfinch is almost certainly the architect of the Bartlett Russell Hedge House located at 32 Court Street, which was designed circa 1800 and constructed in 1803. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it is one of only two buildings in Plymouth highly designed in the Federal-style of architecture. (The other is the Hedge House on the Plymouth waterfront.)

Additionally, the interiors are highly Gothic Revival. Bullfinch had toured Europe from 1785 to 1788, when the latest fad of Gothic architecture was taking hold. Incorporating this new style into an American building was a bold move that set Bullfinch apart. Gothic Revival architecture didn’t reach the shores of the United States until almost 30 years later. Bullfinch was a visionary, a Starchitect of his time.

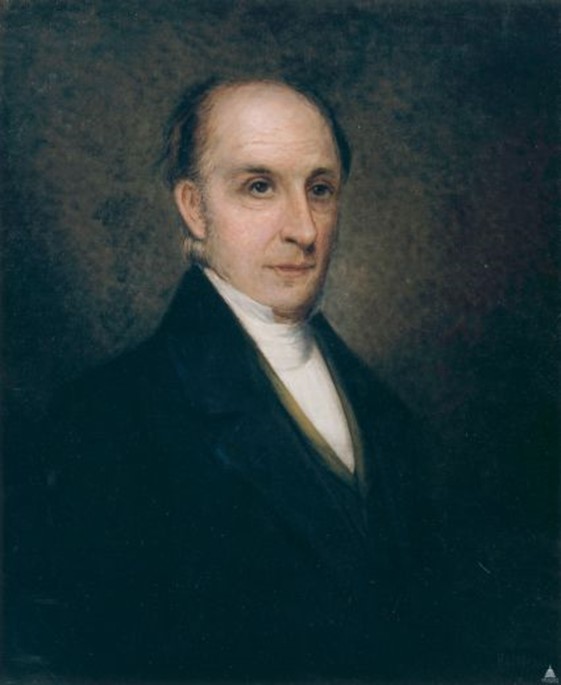

Our next Starchitect was an employee of Bulfinch. Alexander Parris began his career in the Bulfinch office in 1815. Parris was a local boy. He was born in Halifax and started his early career as a housewright in Pembroke. Not long for the South Shore, Parris moved to Portland in Maine, decamping to Virginia and Plattsburg, N.Y., before returning close to home. His tenure at the Bullfinch office was short lived; he opened his own office in Boston in 1818. Shortly afterwards, his career began to take off.

Parris is notable for several famous buildings. They include Quincy Market in Boston, the Barnstable County Courthouse, and First Parish Church in Quincy (The Church of the Presidents). His mark in Plymouth is a building known to all: Pilgrim Hall Museum. The museum was built in 1824 and was designed in Parris’s signature Greek Revival style. It included a street facing gable, Quincy granite, and grand entrance stairs. It’s only flaw is the flaw of all Starchitects: his buildings all began to look the same. I guess the moniker “If it works, leave it alone,” applies in this case.

In the residential world, the mark of a Starchitect is a house that is widely talked about, printed in glossy magazines and repeatedly copied by others. These houses are often groundbreaking. In Plymouth, Samuel Longfellow designed the residence known as Hillside, which was constructed in 1845 on Summer Street. It is recognized as one of the most notable Gothic Revival cottages in the United States and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It has the definitive trademarks of the Gothic style, including steeply pitched roofs, decorative trim, and at one a pastoral garden setting. As the Gothic look spread across America, Hillside was one of the examples to emulate.

The house also hosted important luminaries of the time. Longfellow’s brother was none other than Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Both brothers were visitors to Hillside along with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, William Ellery Channing, Horace Greeley, Louisa May Alcott, and others who were part of the Transcendental Movement. Sadly, Longfellow’s Hillside was a one hit wonder, and he did no further projects.

The exact opposite of Longfellow’s career was one of the most prolific architectural partnerships of the late nineteenth century/early twentieth century: the architectural partnership of McKim, Mead, and White. MMW was headquartered in New York and was established in 1884. The firm existed under its original name until 1928 (when Mead died). The firm is still in business today, although it has a name that reflects the current partners.

I’m a great admirer of their monumental output, particular the residential work they did, much of which was nothing short of masterful. It included many of the Gilded Era estates and mansions in New York and Newport, R.I. Their influence and work were so well known – and still are – that the current HBO show “The Gilded Age” features Stanford White as a regular cast member. (White, a brilliant architect, is also notorious for being murdered in one of the greatest celebrity scandals of the Gilded Age.)

The work of MMW in Rhode Island includes the Rosecliff mansion, the State House in Providence, and the Newport Casino. In Massachusetts the firm was responsible for Harvard Gate, the Boston Public Library, and Boston Symphony Hall.

In Plymouth they designed a landmark structure that millions know and that we’ve all visited or at least driven by. The portico above Plymouth Rock was designed by MMW for the 300th landing anniversary and constructed by 1920. Classical columns and a heavy entablature (roof cornice) were trademarks of MMW and reflected in the Rock’s portico.

In addition to the portico, there is a second MMW structure in Plymouth. The entry gable on Pilgrim Hall Museum was a rework of the 1830s wood portico. It should be noted that Parris’ original building did not include the portico and it was added in 1830 by architect Russell Warren of Bristol, R.I. MMW gave the building the granite portico the building deserved and one that Parris probably envisioned.

I was proud that Plymouth was known for two MMW structures, but what put me on par with my big-city classmates (at least briefly) was another Starchitect-designed building that opened here in 1987, shortly after I had returned home to begin my career.

When the building opened and was covered by the architectural press, I got phone calls from friends. ( Yes, phone calls at my desk because texting was unheard of, and nobody had invented cell phones, email or Facebook Messenger yet. Weird, huh?) The building was the new visitors center at the Plimoth-Patuxet Museums – known then as Plimoth Plantation – and it was designed by Graham Gund.

Gund at the time was one of the architects most in demand and was making a name for himself in the Boston area. When hired by the museum to design the new visitors center, Gund envisioned a New England barn with a central courtyard and a silo re-envisioned as an observation tower. The exterior facade of the building was typical of postmodern buildings under construction at the time and featured exaggerated bulbous concrete columns and oversized squared windows.

Personally, as an architect, I love this building, but as someone who serves up craft cocktails in a part-time bartender gig, I think the building also leaves a lot to be desired. The main function space is interrupted by two structural columns, administrative offices are crammed under sloping roofs, and having no gutters poses all sorts of issues.

In my 20’s, I was enamored by the Starchitects of the 1980’s; today, in my 60’s, I have become very critical of much of their work. My classmates have become critical as well. We discuss bad design, cost overruns, and leaky roofs of the Starchitects we followed in the 1980’s and early ‘90’s. But I’m proud that Plymouth has a great collection of amazing buildings designed by notable architects of almost every major era.

And someday we may have buildings in town designed by Snohetta, OMA, Heatherwick Studio, and Adjaye Associates. It’s OK if you don’t know who they are; I don’t either. But my staff, who are in their 20s, tell me they are Starchitects!

Architect Bill Fornaciari, a lifelong resident of Plymouth, is the owner of BF Architects in Plymouth. His firm specializes in residential work and historic preservation. Have a question or idea for this column? Email Bill at billfornaciari@gmail.com.