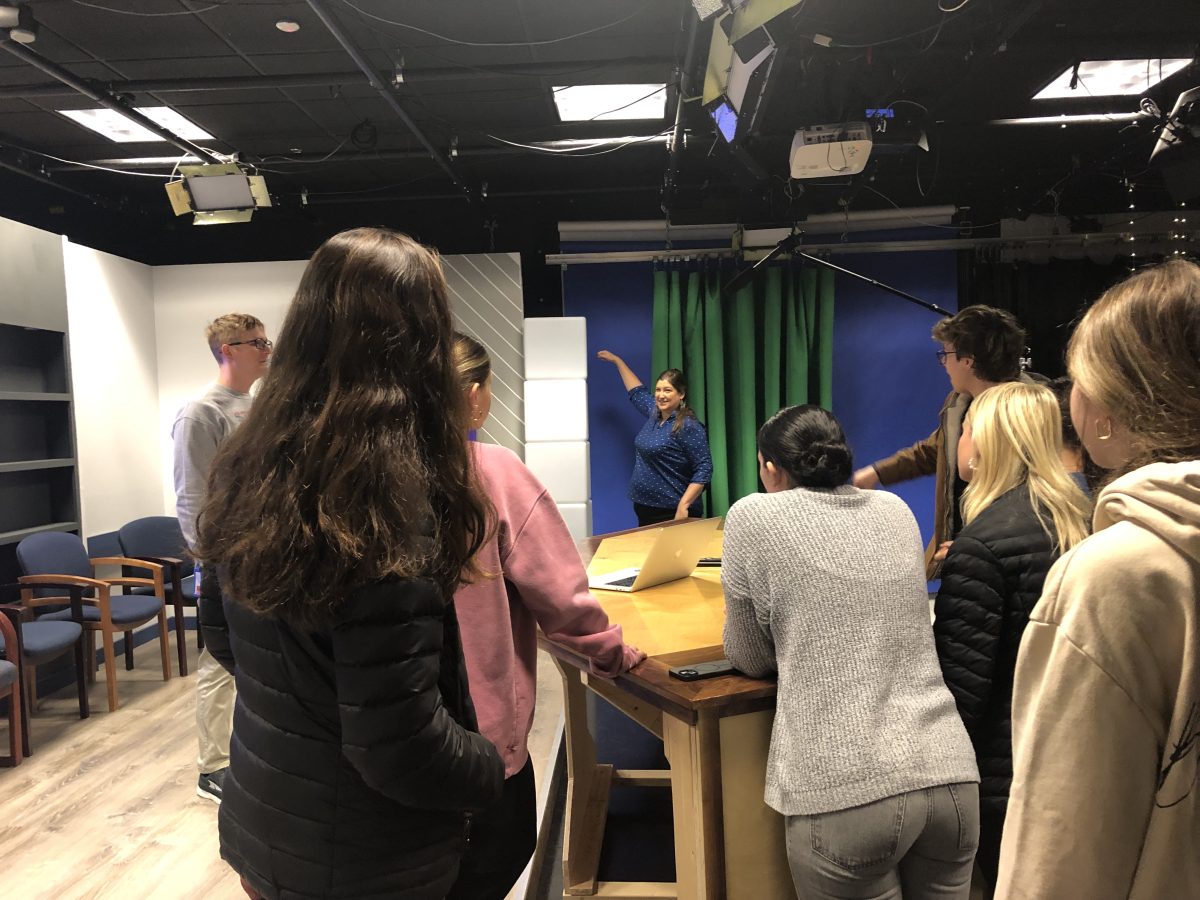

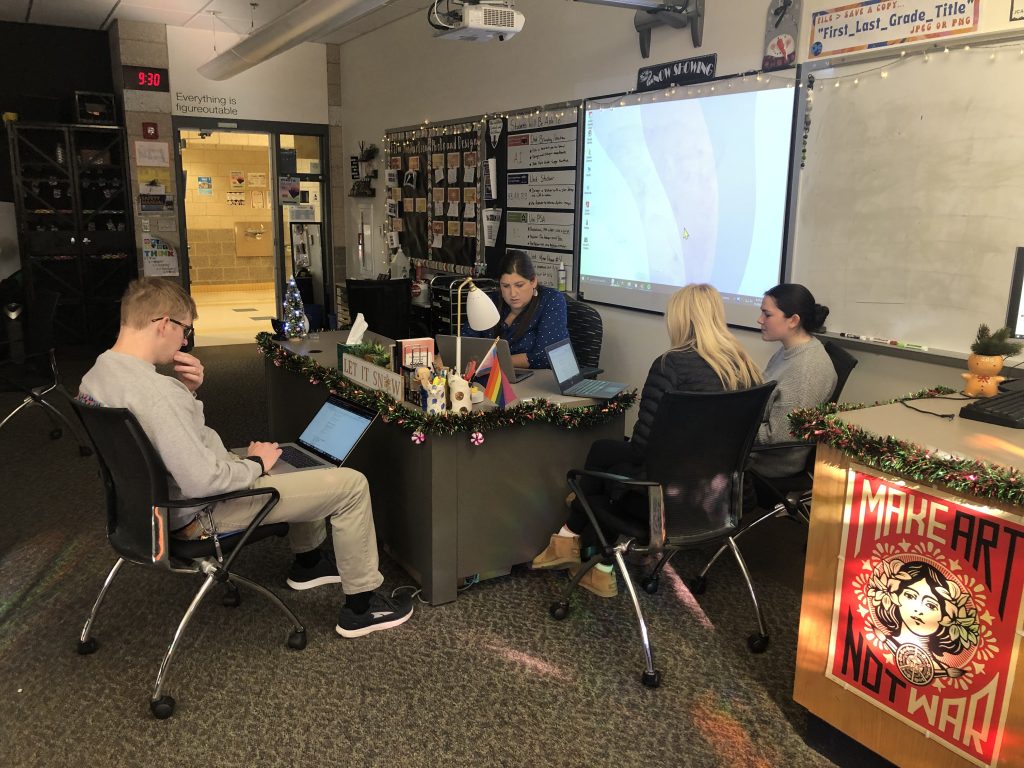

Every three to four weeks, students in Michelle “Shelley” Terry’s broadcast journalism class at North Plymouth High School produce a live 25-minute newscast. They do all the reporting and writing, shoot the video, and run the equipment in the television studio and control room.

People outside of Plymouth have taken notice. The course earned first place recognition from the National Scholastic Press Association for best high school news broadcast in 2014 and 2019.

It earned Terry attention, too. The class was cited as one of the reasons why she received the prestigious Milken Educator Award earlier this fall, which came with $25,000 cash and honors educators across the U.S. for their innovative teaching. Up to 75 teachers will earn that distinction this year. Terry was the first Plymouth Public Schools teacher to get it.

The buzz over her honor hasn’t entirely abated at North.

“She’s totally deserving of the Milken Award, even though she’s embarrassed because we keep bringing it up,” senior Lili Johnson said. “I’m just really proud of her. She’s an awesome teacher.”

Terry teaches the broadcast journalism class with Evan McNamara, education production manager in Plymouth North’s TV/Media department. Terry covers the English aspect, while McNamara deals with the technology.

During a reporter’s visit last week, students were editing video, writing scripts, and editing graphics.

Broadcast journalism is just one of the classes that Terry teaches.

“It’s definitely the most original and different one of all of them,” she said. “Kids are very excited to take the course… It’s very much like a working environment.”

That similarity to a workplace is, in part, what drew Johnson to take the course.

“A lot of skills that you learn in this class are applicable to different careers because you learn how to talk to people,” Johnson said. She added that video editing and graphics knowledge will help her in college, where she wants to study marketing.

Senior Nicole Ryttel, who already liked to write, said she wanted to overcome a lack of confidence in public speaking.

Ryttel likes that Terry is so organized.

“We have very specific checklists that tell us exactly what to do and when to do it and she really holds us to that,” she said. “It’s a good challenge, but it also teaches us a lot about responsibility.”

Gabby Colorusso came to the course knowing that she wants to pursue journalism. Terry herself was also a selling point. Colorusso has taken courses with her all fours years at North.

Terry also teaches Advanced Placement Language and Composition and American Literature. She believes she makes a bigger difference in those classes.

“My greatest challenges and accomplishments are the ones that aren’t celebrated anywhere, which is what is, I think, the deal with most teachers,” she said.

One common challenge is that students come in saying they hate reading and writing, she said. For some, writing a three- to-four-page paper is a struggle, she said.

But Terry persists, finding creative ways to engage them.

She cited a conversation she had with an assistant principal who said a student told him, “I can’t not do the work. She just chases me down. She hunts me down until I do it.”

Colorusso said that until she had Terry as a teacher, she never liked reading. Four years on, she reads for fun.

“At first, she’s quite the intimidating teacher,” she added.

“Throughout the school, most people call her Scary Terry. But then when you have her as a teacher, you realize the humble and intelligent person that she is. That’s kind of what made me want to take all her classes. She explains things well and she cares about her students. She’s strict, but in a good way.”

“She was really scary at first,” said Johnson, who had Terry as a teacher in AP English last year. “But she really got to know all of us. She offered a lot of support for us after school.”

Terry, who heads the English department, said she teaches students who are at two extremes: AP students and students in inclusion classes.

“She has expectations for every type of kid in this building,” said Assistant Principal Pete Parcellis. Terry pushes AP students to excel, he said, “but she does the exact same thing with the toughest kid in the building. Some of our toughest kids who are most at risk, they’ll say that they were pushed by her and they enjoyed her class and they know that she cares about them.”

But it’s not getting any easier. Terry says that cellphones have made it more challenging to get students excited about reading.

“We have to try that much harder to make it more interesting and engaging and get them to want to be interested in class so that they’re also willing to go home and do some work as well,” she said.

Johnson said she loved to read in elementary school, but when she got to high school, it became more of a chore. Terry changed that.

Terry uses different approaches to spark interest in words. When teaching The Crucible, Arthur Miller’s play about the Salem witch trials, she gets student to act out a scene every class period.

“The fact that the kids can yell out the word ‘harlot’ and get excited about recreating those scenes, that’s a great way that I start the year because I think it builds classroom community,” she said. “Then they all start volunteering, because they want to get involved.”

She begins every teaching unit with music. When she talks about The Crucible, she talks about heroes, and students listen to song lyrics about heroes. For Tim O’Brien’s collection of short stories, The Things They Carried, set against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, students will listen to two songs that take place during the Vietnam War – “War’ by Edwin Starr (“What is it good for? Absolutely nothing!”) and Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son.”

“Even if kids aren’t into the actual song because it’s not something they’ve listened to, they’re interested because it’s music,” Terry said.

To keep students excited about reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic, The Great Gatsby – her favorite book to teach – Terry tweaks her approach each year. For one class, she taught the symbolism of colors and the development of characters in the novel. In another, students had to work on a research paper and choose the lens of gender or history. But in all of her classes, her favorite part is when students analyze the original front cover illustration and how it connects to different plot points.

“If you look closely, you can see two naked ladies in the eyes,” she said of the giant eyes that loom over the cover art by painter Francis Cugat. “You can see all the different colors. A variety of dots represents how many people are killed in the book. So that’s a fun lesson. The kids are super into it.”

Terry says that Gatsby, written a century ago, holds timeless appeal for students.

“It has everything that the kids want to know and a serious protagonist with so much going on,” she said. “It’s a love affair. People being murdered!”

She said it doesn’t hurt that she shows clips from the movie version with Leonardo DiCaprio to offer visuals for students who struggle.

In the last two school years, Terry has faced a new challenge that she calls her biggest yet: the rapid evolution of ChatGPT and online artificial intelligence. Students type a question, get a response, and try to pass it off as their own.

”We’re becoming detectives,” she said. “I was in a meeting this morning about it and I’m in a meeting in an hour about it.”

Terry said teachers now have to follow how a paper has been revised, running it through ChatGPT detectors.

“We know when a kid’s voice is very different than what all of a sudden they’ve turned in, but we have to take the time we can to prove it, and it’s frustrating and has changed the last two years of education, especially for an English teacher,” Terry said.

But not all students are tempted to use AI.

Colorusso, for instance, said she does not use it to write.

“Most people have that ability in their brain,” she said. “They just really need to dig through it and not just take the easy way out in writing because most people have great things in their head to put on paper… I’d rather just use my own thoughts because also it’s pretty easy to get caught with plagiarism.”

Fred Thys can be reached at fred@plymouthindependent.org.