We’re now at the forefront of a revolution in how we use energy. It’s being driven by the need to “decarbonize” to slow climate changes and by rapid technological advances in the generation of electricity. We’ve considered “net zero” in this space recently, but it’s important to spend more time with the concept to begin to understand how Plymouth can keep up and even participate in this revolution. Plymouth needs to be involved, but it cannot make a significant difference by itself.

Net zero refers to an international goal to curb climate change that is being implemented at different levels of government, from nations to local communities. Net zero comprises the dual objectives of the reduction and removal of greenhouse gases (especially carbon dioxide, or CO2): decreasing the burning of fossil fuels to reduce releases of CO2 and removing from the atmosphere any CO2 that continues to be released.

When — and if — achieved by 2050, as is the goal, this one-two punch is supposed to prevent Earth’s climate from warming by more than 1.5° Celsius (2.8° Fahrenheit). We’ll still be left with the “baked-in” effects of the 1.5° warming, including increased storminess, extreme heat events, accelerating sea-level rises, migrations of fish and wildlife, among other changes. But, in theory, the Earth shouldn’t be getting any warmer on average.

It’s tempting to let others deal with the problem of global warming, but increasingly parts of Plymouth will be at risk of significant flooding due both to increases in the frequency and intensity of heavy rainfalls and to sea-level rise. Average sea level is expected to be 1.3 feet higher in Plymouth by 2050, according to a projection that takes into account the melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. And what used to be once-in-100-year rainfalls are expected to be four times more likely by mid-century as well.

Plymouth now finds itself on the vanguard of communities that have both recognized a climate “emergency” and have begun planning to alleviate the coming effects. Effective action likely will require efforts at many levels — from individuals to international agencies. And these efforts must work together to reach a net-zero goal.

To this end, Plymouth has established a Climate Action/Net Zero Committee, called the CANZ Committee. It’s made up of citizens who hope to identify and recommend courses of action for the town to move in the net-zero direction. CANZ is a very sensible step for Plymouth.

So can Plymouth achieve net zero for the town on its own? The short answer is no.

Why not?

Even if all Plymouth residents and businesses converted to electric heating and cooking and traded in their gas-guzzlers for electric cars and trucks, the additional electricity to charge vehicles, run machines, and heat homes and businesses must come from a shared regional New England power “pool.” This pool is managed by an organization that works to ensure that the generation of electric power and its transmission takes place reliably across the entire New England region. It goes by the name of ISO New England. ISO is short for “independent system operator.” There are nine such organizations in North America, including two in Canada.

Currently, most electrical energy in the region (49 percent in 2023 through October) is produced by plants powered by natural gas. These plants still release CO2, albeit at levels that are lower than plants powered by oil or coal. So if the residents and businesses of Plymouth today converted all of their heating, power, and transportation uses to those based upon electricity, that power would still be generated in large part by a fossil fuel.

In Plymouth, the only exception to this situation is the residential solar panels (and a few windmills), which do reduce the reliance on fossil fuel generation for the homeowners or businesses who use them for their own energy needs and sometimes to help supply the larger pool.

The good news is that the New England states, acting independently and together, are working to substitute fossil fuel generation with renewable and other clean energy, including most notably solar and wind power. And they have made progress. In 2023 so far, nuclear energy has provided 20 percent of supply, followed by hydropower at 9 percent, and renewables (wind and solar) at 6 percent.

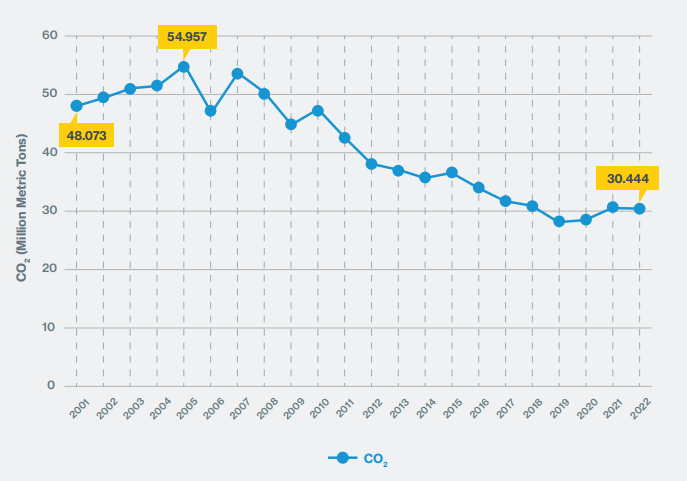

The following chart compiled by ISO-NE illustrates progress in lowering CO2 releases in New England over the last two decades. The units are in million metric tons (a metric ton equals 2,205 lbs). For perspective, national releases of CO2 for power generation in 2022 were about 1.6 billion metric tons, so CO2 releases by electric power generation in New England represented only about two percent of the national total.

This progress is happening primarily through the replacement of coal and oil by natural gas in electricity generation and by increased efficiencies in the production, transmission, and use of electric power. To reach net zero, further progress will need to be paced by a mix of constraints on fossil fuel use, financial incentives to energy users, and building codes.

The constraints comprise so-called state renewable portfolio standards (RPSs), requiring an increasing percentage over time of electricity to be supplied by renewable energy to consumers in each State. The portfolio standards are helping to push what have become rapid advances in renewable energy technologies. ISO-NE foresees large increases in wind and solar energy production as well as the adoption of large-scale battery storage and the expansion of electric transmission lines. Nuclear power (Millstone and Seabrook) and hydropower from Quebec will also continue to be important sources of clean (meaning carbon-free) energy.

The financial incentives involve subsidies at both federal and state levels for individuals and businesses to adopt new technologies, such as heat pumps, insulate walls and stanch air leaks in homes and buildings, and purchase electric vehicles.

Building codes promoting energy efficiency apply to new construction as well as to significant renovations of older structures. (Encouraging the town to move to the most energy efficient building code has become a central focus of the CANZ Committee.)

The role of Plymouth and other local communities is not to achieve net zero independently but rather to keep pace with this regional shift to electrification, where the electricity would be decarbonized. More specifically, for the reduction component of net zero to occur, energy consumers will need to be positioned to utilize electric power generated by renewables instead of fossil fuels in heating, transportation, and manufacturing.

One of the leading roles of Plymouth’s CANZ Committee is to notify developers, builders, those in the construction trades, and residents about the urgency of transitioning to electrification and to emphasize its potential benefits to builders, home buyers and renovators, and businesses. And Plymouth could serve as a role model to municipalities in the region and nationally by moving forward on climate action in this way.

This transition obviously needs synchronization at all levels. One thing that is becoming clear, however, is that it can’t happen quickly enough. Already, scientists have observed that the Earth’s atmosphere has heated to a level of 1.2°C above the pre-industrial annual average. Earth may reach a level of 1.5°C within the next five years—well before the planned net zero date of 2050.

Because of this rapid warming, greenhouse gas removal, the second component to net zero, will become increasingly important. CO2 removals could involve enhancing natural carbon sequestration, such as the restoration or expansion of seagrass beds in estuaries, kelp forests in coastal waters, salt marshes in backbay environments, forests, as well as the introduction of innovative soil management practices in agriculture. On the horizon is the adoption of large-scale (but costly) technologies to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

Although Plymouth’s natural environment comprises many possibilities for increasing greenhouse gas removals, such approaches may well be problematic in a community with a growing population, necessitating coordination on both reductions and removals at regional levels.

Plymouth resident Porter Hoagland is interested in local environmental and natural resource matters. He welcomes your feedback, and he can be reached at phoagland@whoi.edu.