The town and the owner of the Atlantic Country Club have reached an apparent stalemate over the fate of the South Plymouth golf course and the dispute is getting ugly.

Lawyers for owner Mark McSharry last week sent a third letter to the town, this time dropping the veneer of goodwill and accusing officials of acting in bad faith.

The fight may end up in court, according to people on both sides.

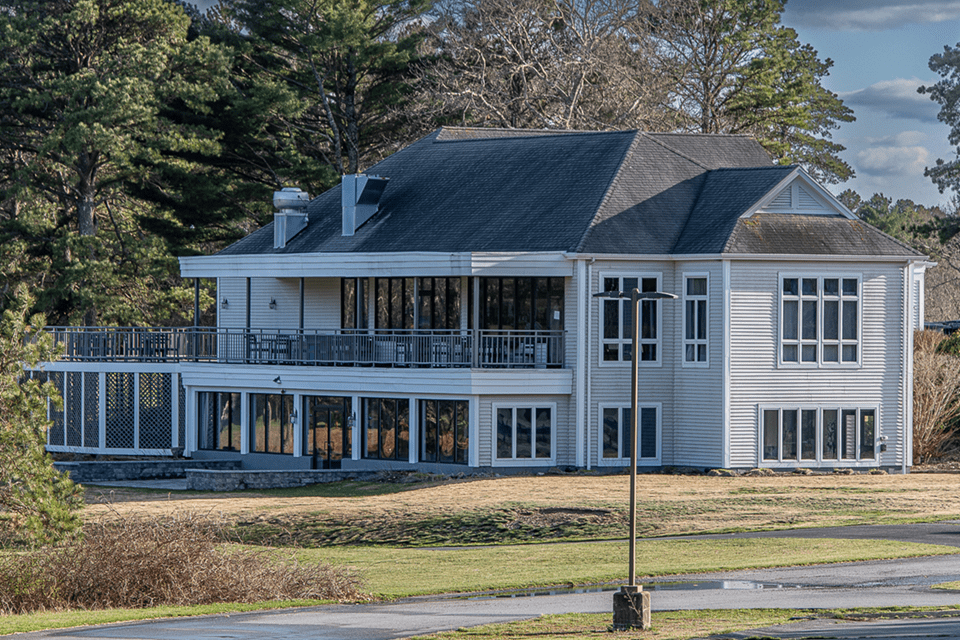

For months, the town has thwarted McSharry’s effort to sell the 180-acre property at 450 Little Sandy Pond Road to a real estate developer for housing. McSharry’s family has owned the club for decades.

A Duxbury developer has offered to purchase it for $20 million, but the town has the right of first refusal, which means it has the option to buy the club. Officials, however, say the asking price is too high.

A notice of intent to sell the property has been batted back and forth between the town and McSharry.

On July 11, McSharry’s lawyer, Kathleen Muncey, suggested the town was engaging in “intentional stall tactics” to delay the sale and hinted that her client may sue if the proposed deal to sell the club falls apart.

“The town’s alleged bad faith, she wrote, “may have unintended consequences should the buyer elect not to proceed because the town refuses to accept” the sale plan.

Since April, Plymouth officials have made it clear that they oppose the likely construction of hundreds of housing units on the site.

That’s when the owner approached the Select Board to see if the town wanted to exercise its right to buy the property for the amount offered by Ben Virga of Duxbury.

Because the land was classified as recreation land and subject to substantial property tax breaks, the town had a right to match any “bona fide” offer. It could also waive its right to buy the property, clearing the way for a private sale.

By law, the town had 120 days to decide. But when that deadline arrived, the town simply sent the paperwork back to the owner. It neither agreed to buy the land, nor to forgo the opportunity.

The town’s lawyer declared that Virga’s offer (since lowered to $19 million) was not “bona fide” because the proposed sale price was “wildly inconsistent” with the town’s valuation of the property.

Plymouth General Counsel Kathleen McKay argued that a legitimate offer must be tied to the current — not the future — value of the land.

That parcel is assessed by the town at $651,325. That number reflects tax breaks the owners received because it was taxed at a discounted rate because it was classified as recreation land.

Even without the tax break, the property’s assessment would be $2.6 million — still far below what the buyer offered to pay, officials said.

But McSharry and Virga believe the value of the land is what a buyer is willing to pay and what an appraiser decides it is — not the depressed value of the property under the recreational land designation.

In June the town sent the plan back to McSharry, saying it wouldn’t act one way or the other until several deficiencies were corrected.

Those included coming back with a good faith offer – less than $19 million – and stating exactly what the developer intended to do with the property.

In her July letter, Muncey did not agree to correct any of those conditions and gave the town until Sept. 18 to respond.

It’s unclear what happens if the town and the owner cannot reach an agreement.

The town could ask a judge to declare that the $19 million price was inflated, or the seller could seek a court order forcing the town to decide — either match the offer or give up its right to purchase the land.

But there’s a plot twist.

McSharry, the owner, has just removed the land from recreation status. That matters because the town’s right of first refusal disappears a year after the property is converted to regular use.

So if Virga is willing to wait, the town would have little or no leverage and the developer could move ahead with plans to build housing on the property — a lot of housing.

Though it is currently zoned for house lots of almost three acres, the developer could opt for a 40B designation — meaning an affordable housing project that could be much larger and subject to little regulation by the town.

Such projects are required to designate at least 25 percent of their units as “affordable.” In return, they can bypass local zoning and other laws.

Virga hasn’t detailed his plans but said he’s willing to hold out for a year, if necessary.

“We’d be happy to wait a year, but there’s no way the seller is going to want to, and our problem is that we support all the seller’s efforts,” he said.

“We feel that we have made a valid, binding legitimate offer that complies 100 percent with the statute. The town needs to either waive the right of first refusal or they need to buy the property for the amount that we’ve offered. Those are their two options.”

Town officials and neighbors have repeatedly expressed concerns that a 40B project with hundreds of homes would change the character of the area and strain town services.

Some residents have urged the town to buy the land — to leave it as open space or perhaps to use as a municipal golf course.

The Select Board discussed the letter in executive session last Tuesday, but chair Kevin Canty declined comment.

Town Manager Derek Brindisi said officials are “reviewing [McSharry’s] response.”

Andrea Estes can be reached at andrea@plymouthindependent.org.