Until a few years ago, Benjamin Dominic’s employment prospects were bleak. Living in rural Saint Rock, Haiti, with no electricity or running water, the young high school graduate had few hopes of becoming anything other than an unskilled laborer.

Today, Dominic is a trained cyber security specialist who helps companies in Plymouth create websites and strategies to keep their Internet presence secure. He’s at the forefront of the AI revolution, mastering new skills, building smart systems, and creating powerful tools that help businesses operate more wisely.

His career path is thanks to Project Trinité, a Plymouth nonprofit that’s enabling young men and women in two remote regions with virtually no access to the digital world find meaningful employment. That, in turns, allows them to support their villages in significant ways.

“Project Trinité has brought an extraordinary change in my life and is making a real impact in my community,” Dominic said in a video posted to the nonprofit’s Facebook page. “It has helped me learn about technology and understand the importance of security in everything we do.”

At the end of his message, he clenches his fist and states emphatically, “We are ready!”

The brainchild of two local businessmen, Project Trinité is making a difference in Haiti and Kenya with portable commerce centers that provide computers, solar power, and Internet connectivity, along with training. These metal shipping containers come with all the necessary systems so people at rural sites with few economic means can reap the benefits of the global digital revolution.

“At these locations, there’s no power or any other infrastructure for miles around,” said Project Trinité co-chair Matt Glynn. “These are bright people who want to work but have nothing. We’re making an impact by providing them with a chance to make their communities better.”

“We wanted to see if we could get technology to work in remote areas,” added cochair Jim Goldenberg. “Could we get them connected to the Internet and working on projects that helped companies improve their systems? We’re proving out that concept now.”

Each 20-foot pod is outfitted with solar panels for electricity, a satellite dish for web access, laptops, desks, TV screens, and even heating and air conditioning. Onsite managers hire staff and teach them how to build websites, write code, set up cyber security programs and become experts in AI, or artificial intelligence.

“We used to provide a class on AI for our teams,” said Glynn, who owned Glynn Electric before selling it in 2022. “But now they know more than us. They created a bot that scans the Internet each morning for the latest developments in AI and shares that knowledge with everyone. It’s amazing.”

A registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit, Project Trinité came about two years ago over a lunch conversation. Goldenberg and Glynn, friends and business associates who share a deep interest inphilanthropy, were looking for a way to help people in undeveloped communities.

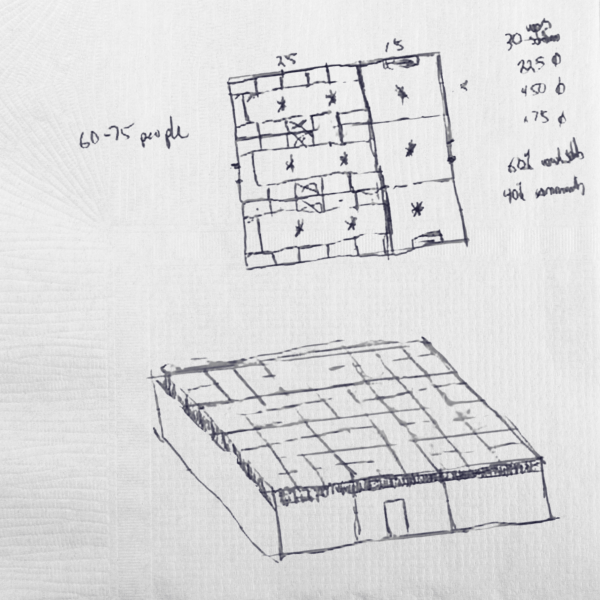

Like many other great ideas, this one began on a napkin. As they chatted about possibilities, Goldenberg sketched a plan for portable offices made from metal shipping containers, powered by solar cells with Internet connectivity.

The napkin showed three large metal shipping containers fastened together. Though that design was later whittled down to just one 20-foot container, it became the working concept for what’s providing a lifeline for people in Haiti and Kenya.

“Once we got going, we realized we didn’t need quite so big a setup,” said Goldenberg, founder and president of Cathartes, a private real estate firm that built Harborwalk Apartments next to Cordage Commerce Center in 2019. “The smaller container works great with room for eight people, though they often fit a lot more in them.”

Today, Project Trinité provides employment for about 50 people. They offer services for the web, cybersecurity, AI, and other areas for companies owned by Goldenberg and Glynn. The two men are sharing their experiences as proof of success, hoping to convince other businesses to let these excited young people help them.

“The associates are super productive,” Goldenberg said of the workers. “They are so excited to learn and work. It’s incredible the things they have done for us so far.”

While creating jobs was the immediate goal, the portable pods are helping communities grow as well. Workers often assist with improvement projects such as wells, roads and other infrastructure projects in their villages. In addition, Project Trinité containers have become sort of a center for civic pride and local development.

“There have been some unintended benefits,” Glynn said. “We’ve seen school attendance and grades skyrocket because students want to graduate and be a part of this. There is no power for about 100 miles around, so people from other villages will drive to these places to see the big spotlight on top of the container at night. This, in turn, has created local commerce as visitors spend money for goods and services in these towns.”

Goldenberg and Glynn have donated tens of thousands of dollars of their own money to get Project Trinité up and running. Both say they believe in giving back some of their own good fortune to make a difference in the lives of others. They are also asking people of means to contribute so the nonprofit can expand into other regions.

“I mean, how much money do you really need?” Glynn said about his own philanthropy, which includes giving to local groups such as the Boys & Girls Club of Plymouth. “Faith is very important to me, so I want to do what I can to help others. I also do it for my son Joshua, who died a few years ago.”

Though they are asking for donations now, Glynn and Goldenberg said that won’t always be the case since Project Trinité is designed to become self-sustaining. Their hope is that it will generate enough income to fund the construction of more portable commerce centers in other countries.

“We’re already looking at South Africa,” Goldenberg said. “We hope to expand there next. It all depends on the amount of seed money we get and the number of businesses that want their services.”

Watching videos on social media gives a clue to the enthusiasm Project Trinité has engendered in young people involved with it. All of them end their brief talk about how excited they are with the same pumped-up expression: “We are ready!”

“The associates just started saying that and it stuck,” Glynn said. “It’s become our unofficial slogan. They are ready to tackle just about any challenge.”

For more information about Project Trinité or to donate, go here.

Dave Kindy, a self-described history geek, is a longtime Plymouth resident who writes for the Washington Post, Boston Globe, National Geographic, Smithsonian and other publications. He can be reached at davidkindy1832@gmail.com.