As a gloomy fiscal outlook descends on Town Hall, there’s added urgency to bolster local revenue to avoid layoffs, service cuts, or a Proposition 2 ½ override.

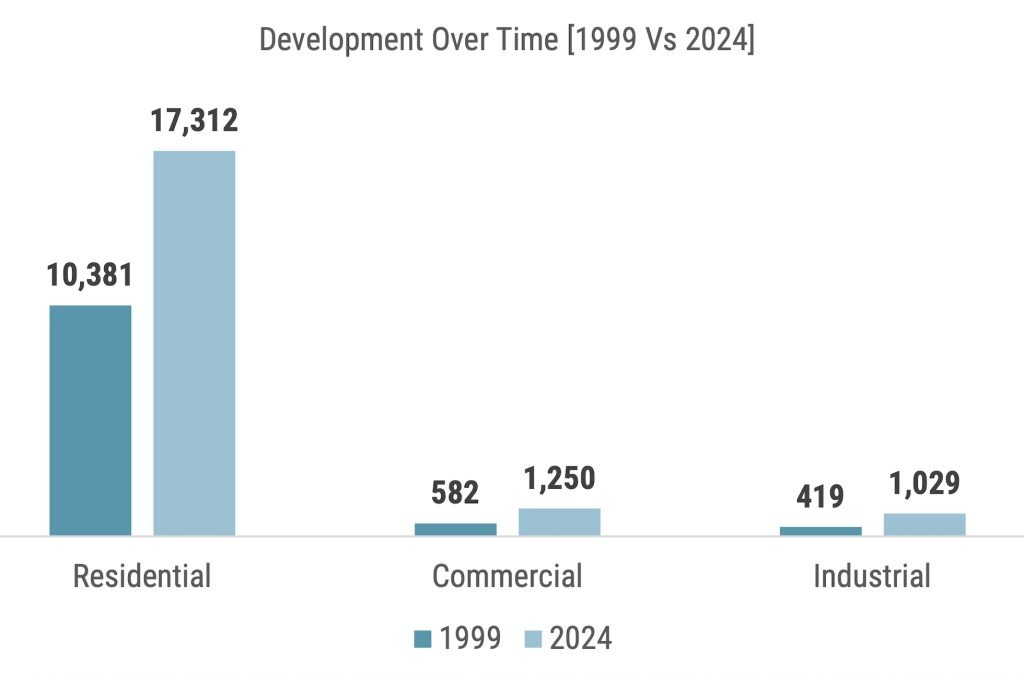

Growing the commercial sector is not a new idea, but it has not been Plymouth’s strong suit for decades. Most of the growth here over the past 25 years has been residential, led primarily by the Pinehills and Redbrook developments.

As those mega projects approach completion, pivoting to business-focused development may be a challenge, observers say. They cite Plymouth’s diffuse leadership, protracted permitting processes, and a surprisingly small amount of land available for commercial and industrial growth.

“People seem to be under the impression that Plymouth has the potential to be overrun with new development,” said Steven Bolotin, chair of the Planning Board and the Master Plan Committee. “The simple fact is, there isn’t that much more land available.”

After months of research and multiple public input sessions, the Master Plan Committee compiled an “existing conditions” report about Plymouth. It documents where things stand in town across many areas, including housing, natural resources, public services, open space, transportation and economic development, among others.

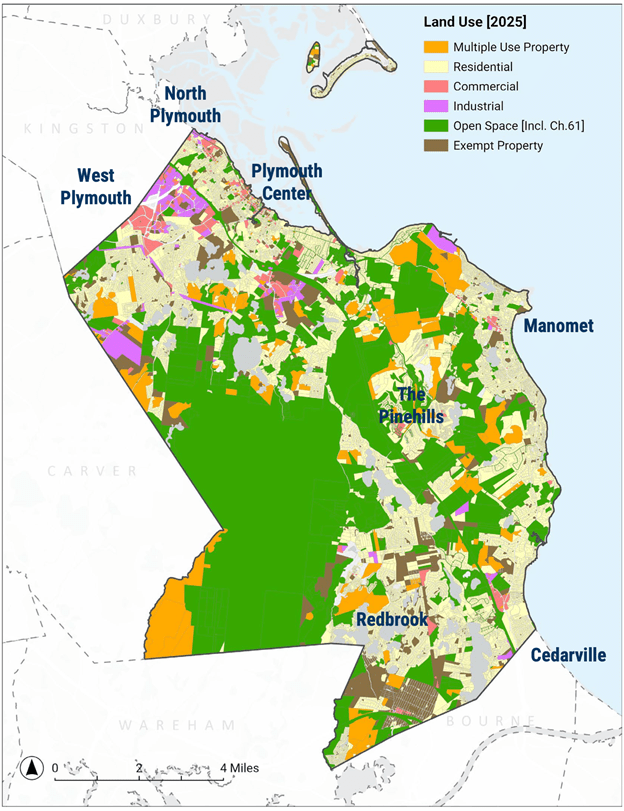

According to the report, Plymouth’s total land area is 65,920 acres. Of that, 28,177 (43 percent of the total) are protected open space, including the massive Myles Standish State Forest, which spans more than 11,000 acres in Plymouth. For comparison, the entire town of Kingston has about 11,900 acres of land.

Residential uses account for 28 percent of the land area in Plymouth. Only 2 percent is zoned commercial, and another 2 percent is zoned for industrial uses.

Looking at the potential for growth, the existing-conditions report found only 2,100 acres of “developable or potentially developable vacant land zoned for residential, commercial, and industrial uses” in Plymouth. And of that total, 1,611 acres are residential, 256 acres are zoned commercial, and 234 are available for industrial development. That means less than 1 percent of the land in town is available for commercial or industrial development.

With such a scarcity of commercial land, Plymouth needs to be more strategic in encouraging development at those sites, Bolotin said.

“We need to decide what kinds of businesses we want to attract to town, and once we identify those businesses, we need to make the process for them to come here more reasonable,” Bolotin said. “When you speak to the business community, both locally and those who had considered coming here, we certainly have a reputation of being difficult to get through our processes and to even understand how things work here. We have many layers of bureaucracy.”

Improving the town’s development processes is not a new idea. In 2016, Professor Barry Bluestone of the Dukakis Center For Urban and Regional Policy at Northeastern University was asked to study the matter. In his report, “A Look at Economic Development: Plymouth, Massachusetts,” Bluestone found that while Plymouth’s culture, environment and quality of life could promote growth, it suffered from classic “deal breakers” that impede development.

“Your jurisdiction’s overall review processes are far slower than [other communities],” he wrote. “Plymouth does not provide a flowchart of the permitting process or a development handbook, nor does it allow for a single presentation of development proposals to all review boards and commissions. Plymouth does not offer fast-track permitting in the form of an overlay district nor pre-permitting for developments.”

Not much has changed since 2016, but many say now is the time to address those issues as Plymouth confronts the need to grow more effectively.

“Our economic development lacks momentum at the moment,” said Select Board member Kevin Canty. “When we talk about smart and balanced development, it’s not going to come out of nowhere.”

In 2001, the town outsourced its economic development function by helping to create the Plymouth Regional Economic Development Foundation, Inc., a private nonprofit corporation. Through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) the town engages the foundation to hire “a full-time Economic Development Director to oversee the Town’s economic development opportunities and priorities…develop and administer a comprehensive economic development strategy for the town to attract new businesses and expand existing businesses (and) manage economic development efforts for the town.”

If a prospective development project comes forward, all planning and permitting processes are coordinated by municipal employees in the Planning and Development Department. Multiple boards have jurisdiction in many cases, including the Planning Board, Conservation Commission, Historic District Commission, and Zoning Board of Appeals. In addition, developers are typically asked to present their plans to neighborhood steering committees for review and recommendations. Town Meeting itself may be involved if there are requests for zoning changes or sale of town land.

It’s a lot to navigate, and may discourage commercial developers from considering Plymouth.

“We need to do more with economic development in Plymouth,” said Select Board member Deb Iaquinto. “We are at a point now where we need to think about a different model, one that includes the foundation and the work they do, but also a focus within town government to be more aggressive on reaching out to attract the kinds of businesses we want.”

To position Plymouth for success in growing its commercial base “the leadership element cannot be underestimated,” said Dennis DiZoglio, an associate at The Edward J. Collins, Jr. Center for Public Management at UMass Boston. “You need the face of the community to be the leader promoting the economic development that the community wants.”

That could be easier with a mayoral form of government, where the top leader is clearly identifiable.

DiZoglio has more than 40 years of public planning and community development experience in Massachusetts. He is a former three-term mayor of Methuen and also served for 10 years as the executive director of the Merrimack Valley Planning Commission, working on regional economic development programs for 15 communities.

While Plymouth has its own special characteristics, DiZoglio said its challenges in promoting and managing economic development are not unique. “There is a stark difference between town government and city government. Cities are much more efficient dealing with development. Towns are fragmented, often with cumbersome, bureaucratic processes that can discourage businesses or developers from participating,” he said.

DiZoglio said Plymouth should look at the specifics of its zoning and consider changes or new overlay districts that would promote the kind of development it seeks.

“You should have a designated person that can guide a project through the permitting process,” he said. “Someone who knows all the players involved and can get people in the room who have the ability to resolve any issues.”

There is an important role for an external nonprofit entity, like the Plymouth Foundation, to assist with economic development projects, DiZoglio said. When he worked in community development in Taunton and Peabody earlier in his career, both cities had associated nonprofit economic development corporations that helped with land acquisition, financing, and construction of industrial parks in those cities.

“With the nonprofits, connection with the local government is key,” DiZoglio said. “There has to be some way to ensure coordination and cooperation with the community’s goals.”

Looking ahead, Town Manager Derek Brindisi expects significant changes aimed at promoting more economic development will come in 2026.

There’s already been a major change in personnel, with long-time Planning and Development Director Lee Hartman recent retirement. Brindisi elevated Lauren Lind, the deputy director of that office, to the top job upon Hartman’s departure last month.

Lind made her inaugural presentation to the Select Board as director on Dec. 30, charting her goals for the department’s various divisions, including a greater role in economic development. On Jan. 20, the Select Board, the Planning Board and leadership of the Plymouth Foundation will meet together to discuss strategies and how economic development in town should evolve.

The timing is urgent, Brindisi and others noted, as the draft of the new Master Plan, with all of its data and suggestions for changes to foster targeted growth and advance the community’s multi-faceted goals, is set to be presented at a virtual meeting on Jan. 8.

“We haven’t had this level of public engagement around economic development in years,” Brindisi said. “The master planning process has been great and I think there will be a lot in there that the community could embrace. So, at some point we have to say we’ve had a lot of public input and it’s time to get to work and make decisions. Are we going to put this plan on the shelf and let it collect dust or are we going to start implementing it?”

Michael Cohen can be reached at michael@plymouthindependent.org.