Confession. I’m a big Jimmy Buffet fan, a true Parrothead. One of my favorite Buffet songs is “Fruitcakes.” It’s a hilarious look at everything from politics to relationships to religion, placing blame for our human condition on the cosmic bakers that took humanity out of the oven too early. Essentially, we are half baked.

When Buffet croons about religion he sings, “There’s a thin line between Saturday night and Sunday morning.” A poetic verse, in my opinion. This plays out in textbook fashion in downtown Plymouth. It’s fully alive on most Saturday nights with patrons packing restaurants and bars. Come Sunday morning, the scene is very different as most folks downtown are quietly queuing for breakfast or attending church services.

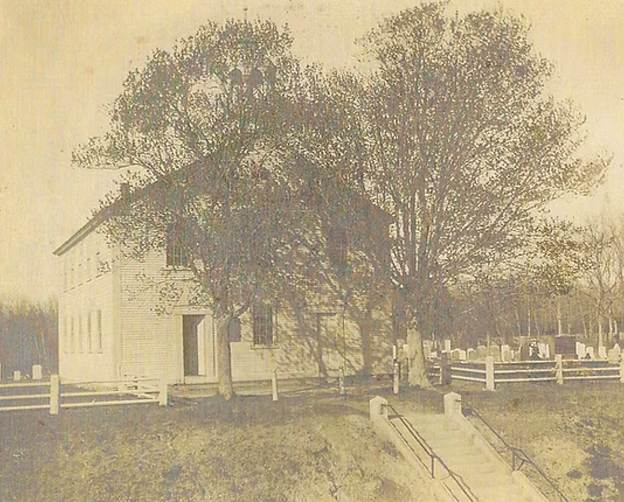

Plymouth has had church services since its founding 405 years ago, but the oldest church building in Plymouth will only celebrate its 200th anniversary next year. The distinction of being Plymouth’s oldest church building goes to the Second Church of Plymouth at the intersection of State and White Horse roads. It was established in 1738, but in 1826 a church was built to replace two old buildings where services had been held. Both buildings originally were on the site of what is now the convenience store diagonally across the street from the church.

The architectural style is Greek Revival which was popular at the time. The building features a gable end facing the street, replicating a Greek temple. Separate front doors and boxed pews were also typical of that period of architecture and while the church retains its original box pews, the separate doors were replaced with one in 1953.

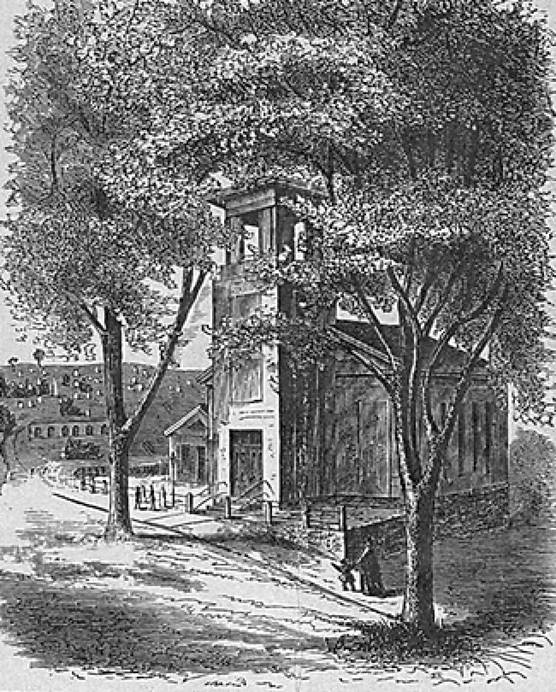

Coming in a close second in terms of age is the Church of the Pilgrimage on Town Square. Constructed in 1840, the building is the congregation’s second structure. In 1800, a new minister called to the First Parish caused a theological rift in the congregation. In 1801 half of its members left to establish the Third Congregation Church of Plymouth. The breakaway members built a church adjacent to the Plymouth Training Green off Sandwich Street. In 1840, the congregation bought land close to its former home in Town Square and built a church in classic Greek Revival style.

In Plymouth, both churches share a friendly rivalry, which became evident when I became president of the First Parish in Plymouth. Gary Marks, then minister of the Church of the Pilgrimage, would often remind me in a good-natured way that “we kept the faith, you kept the furniture.” Gary also offered pastoral services to members of First Parish when we found ourselves without a minister one year.

The third oldest church building in Plymouth is another Congregational church, the Chiltonville Congregational Church at Bramhall’s Corner, built in 1841. Of all the older churches, it’s the one that retains the majority of its original Greek Revival trim. Looking at the front of the building, oversized pilasters (flat columns attached to the building) replicate the columns found on Greek temples. Sadly, the interiors are no longer original, and the space has been divided into smaller spaces.

It’s not surprising that Plymouth doesn’t have a lot of old churches. It’s common in Massachusetts. A scan of the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System shows fewer than three dozen existing church buildings were built prior to 1800. The oldest, Old Ship Meetinghouse, constructed in 1681, is in Hingham. The reason for so few buildings of antiquity may best be described by the fate of F’s – failure, fire, fashion, and finances.

The four fates, individually or combined, usually amount to a death warrant for a building. It’s been a common thread with church buildings in Plymouth and throughout New England since the Pilgrims abandoned the original fort meetinghouse for a more fashionable one. Subsequent buildings were torn down because of aging and the need for more space.

Fire also claimed the 1832 gothic-styled meeting house of First Parish Church in Plymouth in the 1890s. The fire happened during restoration work, sparked by a contractor using an open flame to remove paint. Most churches that burn do so because they are struck by lightning or an ancient heating or electrical systems fails. For example, in 2023 a lightning strike caused a fire that destroyed the 160-year-old Congregational church in Spencer.

Other church buildings in Plymouth have met the fate of the F’s. The Spire Center originally began its life as a Methodist church whose congregation moved on to more fashionable digs. The same can be said of First Baptist Church of Plymouth and the Salvation Army, both of which occupied the gothic stone edifice on Coles Hill until moving to more fashionable and newer facilities. The long-vacant Coles Hill building now faces an uncertain history.

Finances also play a role in the demise of church buildings. Originally, the Unitarian and Universalist congregations in Plymouth were housed in separate buildings. Upon merging for a variety of reasons – including finances – the older Universalist Church (ca. 1822) on Carver Street was demolished.

Finances and system failures also forced the hand of the First Parish of Plymouth. Facing monthly utility bills of thousands of dollars, as well as antiquated mechanical systems, the Norman-styled stone church received a lifeline when it entered into an agreement with the Society of Mayflower Descendants. The society assumed responsibility for the building and is in the process of converting the building to an interactive museum for telling the Pilgrim story.

The story of disappearing church buildings has played out for hundreds of years in Plymouth and in New England, so it isn’t that shocking that our inventory of older ones is dwindling. With three buildings in Plymouth approaching 200 years old, I consider that a win but that doesn’t mean what we have left should be taken for granted. At any time, one of the four F’s could strike, and we could lose another piece of our history. It’s our job to safeguard them.

Architect Bill Fornaciari is a lifelong resident of Plymouth (except for a three-year adventure going West as a young man) and is the owner of BF Architects in Plymouth. His firm specializes in residential work and historic preservation. Have a question or idea for this column? Email Bill at billfornaciari@gmail.com.