I despise this time of the year but not for the reasons you think. As August heads towards September, it heralds the exodus of college students and some of my favorite people are leaving to return to school. That means the “kids” that make my morning latte, the waitstaff at the wedding venue where I bartend, and the J1 visa students in Provincetown – where my husband and I spend a good part of the summer- will soon be gone. I love these folks but may never see some of them again.

In Plymouth, August also means my five-minute commute to work will soon increase by a few minutes as the Plymouth Public Schools will begin the slow roll to opening day.

Plymouth’s public school system operates eight elementary schools, two middle schools, and two high schools in buildings that range in age from well over a hundred years (Hedge and Nathaniel Morton) to less than 10 (Plymouth South High). All these buildings are fairly large and educate multiple students in multiple classrooms, but vestiges of Plymouth’s past endure in the form of one-to-four-room buildings that were once schoolhouses. I know of at least eight, and I’m hoping Independent readers may clue me into a few more.

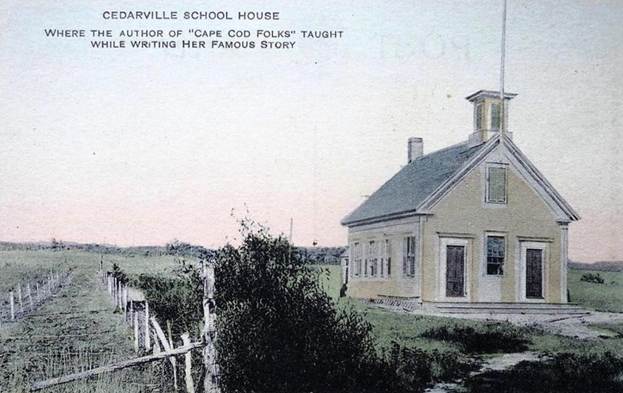

The Little Red Schoolhouse in Cedarville is probably the most well-known. Constructed in 1873, it’s located at the intersection of Herring Pond and Long Pond roads and is one of several surviving one-room school buildings in Plymouth. The Cedarville building is known for having author Sally McLean teach there in 1880. Soon after, McLean wrote the novel “Cape Cod Folks.”It used the actual names of Cedarville residents, leading to what followed was one of the first cases of libel filed against a publisher. The people named in the book won dollar amounts ranging from 50 cents to over $1,000.

The building was a school until 1935 when it was sold. Throughout the following years, it was used for a variety of purposes until 1975 when the town purchased it from private hands and restored for use as a community building.

Further north on route 3A, at the intersection of Bartlett Road, is a close twin – the Manomet Schoolhouse, which is now part of Bartlett Hall, another community building. The original Manomet Schoolhouse is located at the far left of the building. It was reportedly built in 1830 as a one-room schoolhouse. In 1914, it was repurposed as the Manomet library branch. In 1920, the building was moved further back on the lot, away from the street. A large function hall was added to the right of the original building. By 1922, the entire space was converted to a library, a role it would maintain until 1973 when the library moved. Bartlett reverted to a space for recreational uses, and as a youth center.

Continuing north on 3A – and hidden behind Bradford’s Liquor store at the corner of Warren Avenue and Sandwich Street, is the former Wellingsley School building. Originally located in the parking lot on the opposite corner, it was moved and attached to Bradford’s in 1960. The school was built in 1871 and remained in use until 1939. Following its closure, it served as a grange hall until it moved again in 1960 to serve as storage space for the liquor store.

The last schoolhouse on 3A is the former Cold Spring School at 190 Court St. The building was constructed in 1895 as a four-room schoolhouse to replace an earlier two-room school. As the neighborhood grew, the town built the third Cold Spring School in 1951 on Alden Street.

Once students vacated the building on Court Street and began class on Alden Street, the American Legion occupied the former school. In 1955, the town sold the building to the Church of Christian Scientists. A massive remodel would result in the building that stands there today.

The last officially documented schoolhouse is the South Pond Schoolhouse at 203 Long Pond Road. It was built in 1843, making it one of the oldest surviving school buildings in Plymouth. The school served children in the Great South Pond and Boot Pond areas until the late 1920s. In 1930, it was sold and converted to a home.

There are other former school buildings in Plymouth that have been moved, but their histories are not fully documented. They include 356 Sandwich St., 100 Sandwich Road, and 61 Cliff St. My history squad mates have tipped me off to even more buildings. Local historian Jim Baker suspects 144 Summer St. may have been a school, and town archivist Conor Andersen has identified the original Gurnet School, which is now used as a cottage. I have no doubts that there are more.

As early as 1803, Plymouth had established 10 school districts, each of which was required to have a building. The surviving Cedarville, Manomet, Wellingsley, and Cold Spring schools replaced early buildings, leaving me to speculate that other replacements for the 1803 buildings may still be standing.

One such building was the original Oak Street School. Constructed in the late 19th century, it was replaced in 1900 by the building that currently stands at 10 Oak St. and last year was converted to apartments. The original building was rather unceremoniously dragged across the street and converted to a garage. It recently faced the wrecking ball. An unfortunate loss.

As Plymouth kids return to school on Aug. 27, remember that less than 200 years ago students would make their walk to and from one- and two-room schoolhouses all over town. These buildings had rudimentary heating systems, if any, just one teacher, and students ranging age from 6 to 16 learning together. I hope we can fully document the history of these buildings. If I missed one – or you can confirm some on the list – drop me an email. I look forward to hearing from you as I break in a new barista.

Architect Bill Fornaciari is a lifelong resident of Plymouth (except for a three-year adventure going West as a young man) and is the owner of BF Architects in Plymouth. His firm specializes in residential work and historic preservation. Have a question or idea for this column? Email Bill at billfornaciari@gmail.com.