Alfred R. Turner Jr. rowed like he had never rowed before. Pulling desperately on the oars of his rowboat, the wealthy industrialist from Newark, N.J., watched as a 30-foot wall of fire engulfed his spacious summer home on the shores of Little Long Pond. Driven by a 70 mile-per-hour gale 125 years ago, the massive blaze roared out of control across the southern half of Plymouth, consuming just about everything in its path – natural and manmade.

With his family on board the boat, Turner headed to the middle of Little Long Pond as what became known as the Great Fire of 1900 raced around the shore. From there, he rowed downstream along an unnamed brook as the fire raged on both sides of the tiny inlet, finally making his way to the larger and safer confines of Long Pond. The Turners then joined other suddenly homeless families at Hatch Farm, protected from the blaze since it stood in the middle of a large clearing away from trees.

“As they went, they watched their house burn to the ground,” wrote Ruth Gardner Steinway, a Plymouth historian and wife of the president of piano company Steinway & Sons. She was 10 years old at the time of the massive blaze.

For four days in September 1900, Plymouth was in the merciless grip of Mother Nature. Winds from a hurricane that killed 6,000 people in Galveston, Texas, a few days earlier whipped up a four-mile-wide wall of flames in what would become the town’s worst natural disaster.

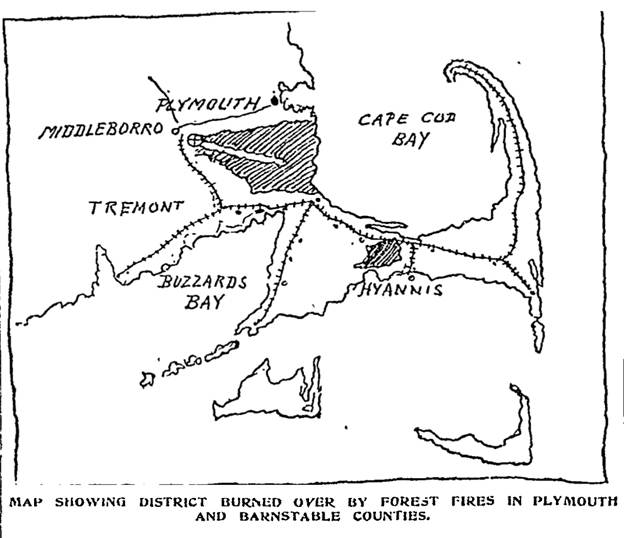

It erupted at College Pond at the western edge of town on Wednesday, Sept. 12, and raced eastward to the ocean at White Horse Beach. The fire then turned south, obliterating tens of thousands of acres of woodlands, meadows, farms, homes and even a whole village. It finally ended late on Saturday, Sept. 15, when tropical rains from the dying hurricane doused the flames.

Today, little is remembered of this immense inferno that left behind large swaths of smoldering ash and caused more than $3.7 million in property damage in 2025 money. An examination of local and Boston newspapers, as well as written accounts by people who survived the Great Fire of 1900, tell an alarming story of danger and destruction that could easily be repeated in modern times – with more devastating effects.

The summer of 1900 had been a dry one. Rainfall was well below average for most of the northeastern United States. In Plymouth County, total rainfall for August 1900 was about 2 inches below normal. Coupled with a lack of snow over the previous winter, the town was ripe for a catastrophe.

According to the U.S. Census, only 9,592 people called Plymouth home in 1900, compared with 64,356 last year, according to a federal estimate. Back then, most people lived in the northern part of town. Fewer resided in the southern half, which today features several large residential developments, including The Pinehills.

In 1900, the Plymouth Fire Department had a full-time staff of more than 30 men. But its main concerns were the town’s buildings and houses. It only fought wildfires when structures were threatened. Instead, Plymouth relied on a cadre of Fire Wardens, who recruited hundreds of individuals to deal with the near-constant threat of blazes in the town’s large and untamed forests of pitch pine and scrub oak.

The summer of 1900 had been a dry one. Rainfall was well below average for most of the northeastern United States. In Plymouth County, total rainfall for August 1900 was about 2 inches below normal. Coupled with a lack of snow over the previous winter, the town was ripe for a catastrophe.

The Great Fire of 1900 technically began on Sept. 6 when a large blaze broke out near a cranberry bog at Sampson Pond in South Carver and moved rapidly into Plymouth, propelled by strong winds. Two days later, firefighters knocked down the flames at College Pond in what is now Myles Standish State Forest, which was not established until 1917.

At least they thought they had stopped the fire. On Sept. 12, still-smoldering embers reignited when hurricane-force winds – remnants of the same storm system that killed so many in Galveston – raged over southern New England. Because of the dry conditions, wildfires sprang up across eastern Massachusetts and Cape Cod, though the worst by far was in Plymouth.

By late morning, western skies filled with a towering column of smoke that could be seen from the Plymouth waterfront. “[F]ew realized then how widespread that devastation would be, nor that pretty lake and seaside cottages, situated miles away, would be only glowing coals within a few hours, while their owners had to take desperate measures to save their lives,” reported the Sept. 15 issue of the Old Colony Memorial.

For the next four days, smoke and ash would occasionally descend on the downtown, giving rise to fears the fire was headed in that direction. At night, an eerie red glow in the western sky hinted at the devastation being visited on the forests and families that lived in the path of the inferno.

Those who fought the fire experienced firsthand its frightful fury. As the blaze approached, they could hear the loud roar of the fire burning through dry brush, undergrowth and woods, and even explosions as trees burst into flames. As the firefighters cleared breaks and built backfires, they felt the intense heat of the inferno as it incinerated forests and farms at an alarming pace – sometimes as fast as two miles an hour. At one point, flames raced from Old Sandwich Road to Ship Pond – a distance of about four miles – in just 30 minutes.

The fire fanned out east and south from College Pond. On Wednesday afternoon, winds from the west drove flames toward the Six Ponds area – Bloody, Gallows, Halfway, Little Long, Long and Round ponds – where summer homes and farms were scattered along those shores. The first to go was the vacation residence of William S. Bassett of Boston. As the fire approached, he helped his wife, who had an injured knee, into a horse-drawn wagon along with a nurse and his children and sent them fleeing to safety in Buzzards Bay.

Bassett’s hired hand, Robert Thompson, his wife and a “servant girl” barely escaped. They had stayed behind until they heard the “wild roar” of the forest fire, according to the Boston Journal. They jumped in a wagon and while the women covered their heads with wet blankets, Thompson whipped the frightened steed through the flames. All of them, including the horse, suffered burns.

As the fire bore down on the home of Joseph A. Brown, he told his wife Cynthia – who was “a very large woman,” the Boston Globe reported – that it was time to leave. She collapsed upon hearing the alarm and died of a heart attack. Incredibly, Brown was the only fatality. Many others would suffer serious burns and injuries from fighting or fleeing the flames.

Other houses and cottages were quickly consumed, including the Turners’ as they rowed to safety. Just before Charles Woodward’s home burned, he helped his wife, recovering from a “severe” operation, into a carriage, then pushed it into the pond for safety. They escaped with a few pillows and the clothes they were wearing. Nearby, the homes, stables, and boathouses of “Mrs. Albert Cooper of Roxbury. Mr. Middleby and Mr. Peterson of Boston” were lost to the inferno, according to the Old Colony Memorial,

As the fire bore down on the home of Joseph A. Brown, he told his wife Cynthia – who was “a very large woman,” the Boston Globe reported – that it was time to leave. She collapsed upon hearing the alarm and died of a heart attack. Incredibly, Brown was the only fatality. Many others would suffer seriousburns and injuries from fighting or fleeing the flames.

Tragedy nearly befell fire wardens George R. Briggs, Gustavus Sampson, Elkanah Finney and an unnamed employee of E D. Jordan Jr., son of one of the founders of Jordan Marsh department store. Caught in the woods, they were surrounded by the fire when it changed directions. They got away, but just barely.

Briggs would not escape unscathed. The former math tutor at Harvard University and author of a geometry textbook now found himself fighting the fire as it surrounded his home, farm, and cranberry operation. The blaze destroyed nearly everything he owned – easily the largest loss in Plymouth.

Before the house caught fire, the family placed valuables in boats and set them adrift on Halfway Pond. One of the possessions was an upright piano, which caused the boat to capsize.

Steinway later wrote, “Legend has it that the piano drowned!”

Cranberry harvesting had already begun at bogs across Plymouth. Scores of pickers and other workers scrambled from their camps to safety, many diving into ponds, reservoirs and bog trenches to escape being burned.

At Briggs farm, 18 women were laboring in the screenhouse when the fire struck. Firefighters led the workers – along with Briggs’ family – to a flume between a reservoir and one of the bogs, then released the water to soak them down. Still, some of the women had singed hair and clothes from the roaring flames.

Rose Briggs, George’s daughter, who was 7 at the time, later remembered taking refuge in the flume with her mother and 5-year-old brother:

“The fire swept down on us with a sudden change of near-hurricane wind,” she wrote. “My father, with the fire wagon and all the men who had any firefighting experience were already out fighting it. The shift of the wind put the main fire between them and home… The fire swept over the place, and finally into the sea at Ship Pond. No one was hurt, but when my father and the men got back, nothing was standing but the hen house and the cow barn… That night we ate half-baked apples off the scorched apple trees. There was nothing else.”

Unfortunately, one of Briggs’ farmhands had moved his belongings from his cottage into the screenhouse. Flames bypassed the home but destroyed the screenhouse and all of his possessions.

Despite his personal loss, Briggs never stopped fighting the fire. With assistance from his brother, LeBaron Briggs, first dean of men at Harvard College, he worked tirelessly for four days in a vain attempt to prevent more farms and homes from being lost.

“His work was, therefore, purely unselfish,” neighboring farmer George Barker told the Boston Journal. “[H]e is certainly entitled to the thanks of the community for what he did. He fought the fire with the greatest heroism… while he worked, his own place was destroyed.”

Barker’s home and farm buildings were saved thanks to Briggs and a bucket brigade of Portuguese bog workers, who kept the roofs wet enough to prevent embers from catching.

At Island Pond, Alma Ann Youngman was warned that the inferno was closing in on her large summer home. She ran inside to grab some of her possessions, then headed back to the door to leave – only to find that flames had surrounded the house. She ran through the fire to the pond for safety with the blaze “scorching her hair,” the Old Colony Memorial noted.

When the fire reached White Horse Beach late on Wednesday, Sept. 12, the wind shifted and pushed the blaze south. Mrs. Walter L. Chase and her daughter were picking cranberries near there when they were suddenly trapped by flames. “Their only chance was to dash into a pond hole, where they remained for a long time before the danger was past,” reported the local newspaper.

Fire also threatened the old Cornish Tavern, now known as Rye Tavern. Built circa 1792 on Old Sandwich Road, the former stagecoach stop lay directly in the path of the raging inferno. Fire crews arrived just in time to divert the flames by digging trenches and clearing away brush.

The villages of Manomet, Vallerville and Ellisville were largely spared as the wall of flames moved down the coast Thursday and Friday. But the tiny hamlet of Thrasherville near Indian Brook was not so lucky. Eight families lived in the settlement, located between Manomet and Ellisville on Old Sandwich Road. All the structures were lost in the blaze, and the small community was never rebuilt. Today, a few overgrown depressions where the houses once stood are all that remain.

As the fire raced south toward Bourne and Wareham, Plymouth residents living along the shore of Cape Cod Bay headed to the beach for safety – as did Frank H. Amsden and his two sons. The Bridgewater residents were picking cranberries at a bog next to Ship Pond near Surfside Beach when the fire struck. They fled the flames and then disappeared. On Friday, Sept. 15, a dory containing their clothes and other belongings – but no Amsdens – turned up in East Dennis. At first, they were thought to be dead, however, the three were found alive and well on the beach in Ellisville. Strong winds had pushed their dory out to sea before they could clamber in it.

Also at Ship Pond, a schoolhouse burned to the ground, leaving only the stone foundation and flagstaff still standing. It was uninsured and would cost the town $1,000 – nearly $40,000 today – to replace it.

George Griswold could only watch as his home and possessions were consumed by flame. He was left with the clothes he was wearing, though the hat on his head caught fire.

Flames licked at the home of Ernest B. Jones, blistering the paint on the side of the building and melting a lead sink pipe. His house was saved, but a nearby shed was reduced to ashes. Also destroyed was a screenhouse full of freshly picked cranberries, a loss of about $1,500.

Concern arose that two young girls had died in the blaze. On Thursday, Bessie and Lillie Bennet, ages 10 and 11, had left their home on Halfway Pond to witness the destruction along Little Long and Long ponds. When they didn’t return, the worst was feared. They were later found safe several miles away at Bump Rock Road.

For most of the time, fire crews had little luck in stopping the inferno. Backfires and firebreaks were employed frequently but the high winds sent embers flying over those obstacles to land on virgin trees and set them afire. On Friday, Sept. 14, firefighters finally gained an upper hand as winds began to abate. Most of Cedarville was saved, thanks in part to a soggy boundary created by Little Herring and Great Herring ponds.

Still, the blaze kept moving south. At noon on Saturday, an alarm was sounded in Onset as the wall of flames crept ever closer. Firefighters made a stand at Muddy Pond near the East Wareham village and stopped the blaze just as the wind was shifting again. Now the weakening gale was blowing westerly – back toward where it started. Covering already scorched land, the flames began to die down.

Finally, at around midnight, rain started to fall from what was left of the Galveston hurricane, dousing the flames and preventing further damage. By 4 a.m. on Sunday, Sept. 16, the blaze was mostly out, and fire wardens could send their exhausted crews home.

The damage, however, had already been done. According to reports, half of the town had been incinerated. Most of the woodlands and many of the homes south of a line from College Pond to White Horse Beach had been turned to ash and charcoal. The Sept. 17, 1900, Boston Globe reported:

“A Globe man today drove from Ship pond into Wareham. a distance of more than 2 miles, and everywhere there was a black mass of burned woodland. The greater part of the burned district was covered with a growth of scrub oaks and underbrush, but there was also destroyed some of the very best pine wood in the town.”

The Old Colony Memorial described it this way:

“For miles the ground is clear of all vegetation except the slender scorched trunks of pines or oaks, bare of leaves and offering no shelter from summer sun heat. Not a living wild thing was seen in all that region by a reporter who traversed it. It was a picture of utter desolation without a sound except the crash of some falling tree or the sigh of the wind through the seared and blackened branches.”

That Boston Globe claimed that “nearly 60 square miles was burned.” That’s probably an exaggeration, given that the town has a total of 96.5 square miles of land, according to the U.S. Census. Even so, if 50 percent was scorched, that puts the total at more than 48 square miles, or about 30,700 acres. Some experts today believe only 35 percent of Plymouth burned, about 21,000 acres – still a significant amount by any standard. The loss by the forestry industry for pine and cordwood was incalculable.

Damage to property was high but not as bad as it could have been. The Old Colony Memorial placed the value of loss at $93,700, about $3.5 million today. Most of that was for large homes and farms that could afford insurance; many owners of tiny cabins did not have any coverage and lost everything. The town had to outlay an additional $10,000 – more than $375,000 today – to pay crews for fighting the fires.

The local newspaper listed 22 property owners who suffered at least some damage during the Great Fire of 1900. Some filed claims for the loss of summer homes and other buildings and their contents, including Alfred Turner, $13,000, William Bassett, $5,000; William B. Youngman, $5,000, Mrs. Albert Cooper, $2,000; Mrs. Middleby, $1,500; Edward C. Turner, $2,000; William S. Leland, $5,000; Linda M. Ellis, $2,000; and William Lake, $1,500.

Farmers reporting losses included Charles E. Woodward, $2,000; Joseph Savery, $1,500; James T. Thrasher, $1,500; and B.W. Harch, $1,500.

By far, the biggest loss belonged George Briggs at $41,000. He lost his home, various farmhouses, stables, horses, vehicles, tools and machinery. Nearly everything he and his family owned was destroyed in the blaze.

For a while, the Briggs were concerned they had lost the family dog, Jerry. The large mastiff was missing and presumed dead. Jerry was eventually found submerged in a brook with his nose above the waterline.

“He was all right and had taken all precautions for his safety,” the Old Colony Memorial wrote.

Which begs the question: Has Plymouth taken precautions to deal with a future fire of similar scope? The town is still heavily wooded, and a comparable blaze today could cause significantly more damage and threaten many more lives – consider, for example, all those homes in the once undeveloped Pine Hills area.

It’s scary to contemplate but combine thousands of wooden structures near each other with increasingly intense weather events linked to climate change – along with limited firefighting resources – and the potential for an unimaginable catastrophe is undeniable. But does it have to happen? Are there ways to head off such a disaster in Plymouth?

Editor’s note: In part two of this story, town officials and others will address the question of what is being done to prevent another deadly firestorm.

Dave Kindy, a self-described history geek, is a longtime Plymouth resident who writes for the Washington Post, Boston Globe, National Geographic, Smithsonian and other publications. He can be reached at davidkindy1832@gmail.com.