I wouldn’t recommend taking a shower at Memorial Hall.

The stalls sit behind frosted glass in a cramped hallway leading to a dank dressing room – not exactly luxury accommodations. A pallet of anti-bacterial soap couldn’t get me to step in there.

That was one of my takeaways from a recent tour of the 100-year-old town-owned venue. I went at the invitation of Town Manager Derek Brindisi, who has warned that Memorial Hall will have to be shut down within two years if action isn’t taken to repair serious structural flaws. Based on what I saw, he’s not being dramatic.

That’s why the town is pushing a four-stage plan to save it. A consultant’s report, which includes some extras that seem more like essentials, pegs the total price at about $28 million. But the report, presented to the Select Board only weeks ago, is already outdated. (You can view that slide deck here.) Brindisi says the projected cost is now closer to $34 million.

Even that amount won’t be enough to turn the building into a state-of-the-art venue, but it will keep the lights on and create a better “experience” for audiences. That’s crucial for Plymouth’s economy – and culture.

The town initially hoped $15 million toward the project would come from Community Preservation funds, if Town Meeting agreed. But following a presentation at a July 23 Community Preservation Committee meeting, some members, including Select Board representative Bill Keohan, questioned whether it’s a wise use of the CPC’s limited funds.

On Tuesday, the Select Board pumped the brakes, deciding to table the request to the CPC, which votes whether to recommend such spending. Instead, Select Board members are calling for an outside study to determine how much of the proposal meets the “historic preservation” requirements of state law. (See Fred Thys’s related story.)

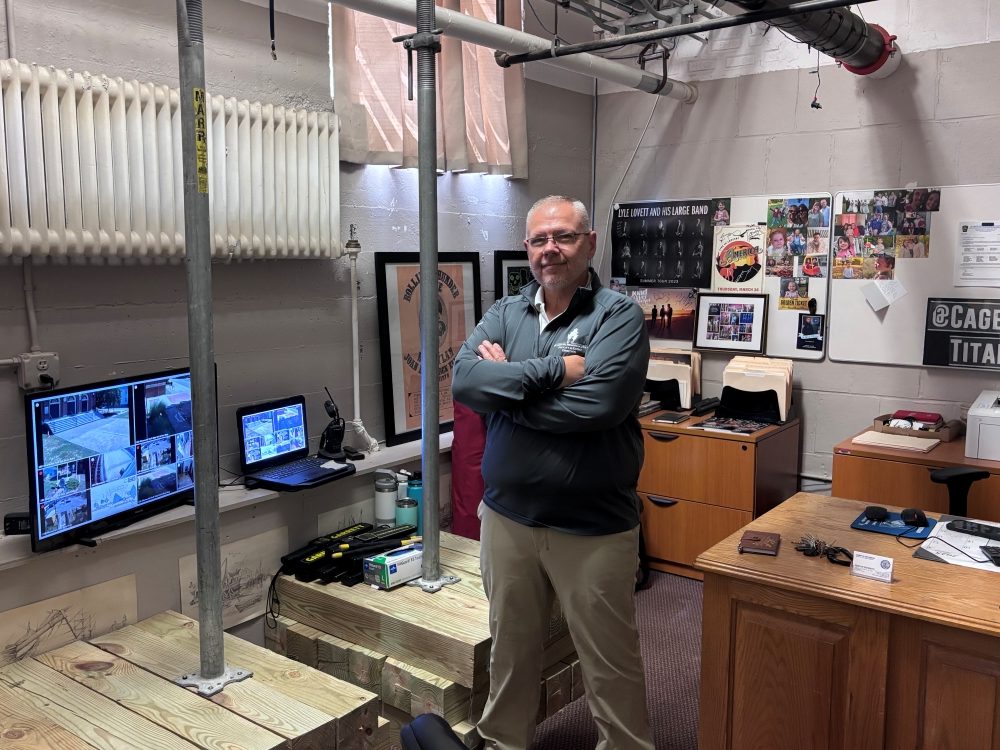

During the tour, Brindisi and I were joined by Joe Goldberg, the hall’s events director and facilities manager, and Karl Anderson, the town’s facilities manager. All three were candid about what it would take to renovate the building.

Memorial Hall’s problems have been worsened by years of neglect, some partially hidden by patchwork fixes. It’s akin to a homeowner putting off major repairs until they add up to a crisis.

For example, an analysis using infrared technology found water was “infiltrating” the building in several areas, but according to an outside firm’s report, “no professional remediation” actions were taken.

That was 14 years ago.

Other issues include an ancient heating system powered by “two giant gas furnaces that were probably put in in the 1950s or ‘60s,” said Anderson. “They’re about the size of a school bus.”

Surprisingly, air conditioning keeps the building “extremely cool…when it’s working,” Goldberg said. I stopped by Wednesday morning – sure enough, it was cool as a cucumber, even though the front doors were open.

“The issue we have with both systems is that there’s no thermostat. It’s either on or off,” he said. “In the wintertime, people on the floor say, ‘we’re freezing,’ but it’s 100 degrees up in the balcony. There’s no air movement.”

Replacing those dinosaurs with an energy-efficient HVAC system could cost about $5 million, Brindisi said.

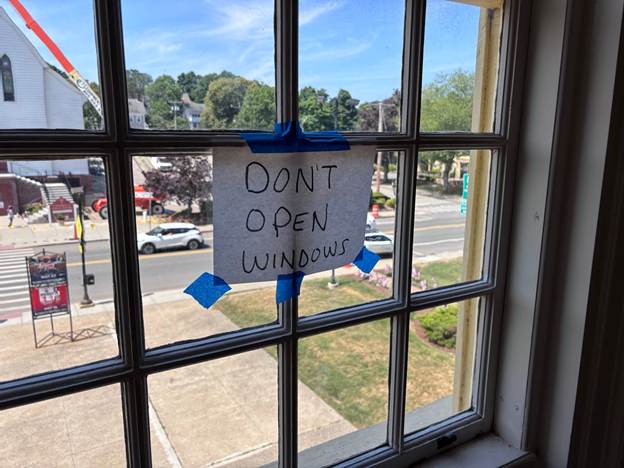

Other issues include windows that can’t be opened for fear they will fall out, limited stage access that makes it impossible to host major theatrical productions, poor acoustics (despite an upgraded sound system, the hall is basically a gym), uncomfortable seating, subpar concessions stands, inadequate bathrooms, a shallow stage that can’t fit the Plymouth Philharmonic and other large groups, a roof that needs replacing, and a cramped dressing room more suited for CIA interrogations.

And then there’s the water.

Goldberg led me into an electrical room that showed obvious signs of past flooding. You read that correctly – water and electricity together.

An adjacent hallway sometimes gets covered with “about an inch and a half of water,” he said. Nearby, it can get three inches deep.

“It actually comes out of the electrical panel,” Goldberg said. “It comes right through the wall.”

Anderson said an electrical inspection revealed “some minor corrosion and damage [that] we’re going to have repaired immediately.”

“It hasn’t created an issue – yet,” Goldberg added.

In his tiny office on the lower level, metal poles propped on wood provide support. The same stopgap setup is used in the artists lounge, a space whose worn recliners made me want to reach for a can of Lysol.

The water damage doesn’t just come from rain permeating the walls. Like most of the downtown area, streams run under buildings to the sea, something property owners in the area have dealt with for centuries.

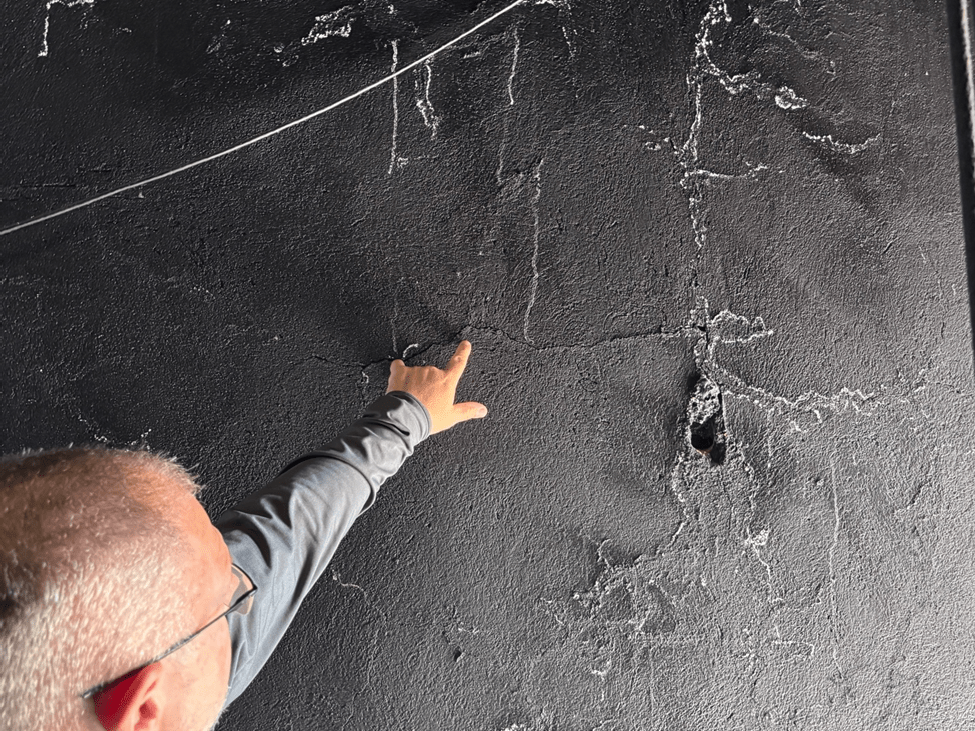

Behind the stage, work to remove a crumbling cement covering on the rear brick wall earlier this summer prompted Brindisi – under pressure from the DPW union- to close the hall for more than a week after a contractor inexplicably used a leaf blower to “clean up” the dust. It caused a mess and raised health concerns. Testing showed that the air was safe, just in time for a Graham Nash concert.

Without the cement covering – which was considered a hazard – more rain will get inside the backstage area. Anderson said that prior to its removal, a “water intrusion test” showed that after six minutes of a gentle exterior spray (at 11 psi), “you could see water coming through and sheeting down from up top.”

It’s another flaw to blame on neglect. The building was supposed to be “waterproofed coated” at least every 10 years, Goldberg said. The last – and only – time that happened was in 2009. Imagine what further damage major storms could wreak. Or already have deep inside the walls.

Which leads to a reality check: Can Memorial Hall be saved? Should it be?

A noble idea could quickly turn into a money pit. Anyone who’s taken on a home renovation project has heard a version of this line: “We don’t know what we’ll find when we start taking things apart.”

Translation: Fixing the building is going to cost more than the current estimate.

Not every older building is a good candidate for an expensive restoration. This may be a minority opinion but sentimentality aside, Memorial Hall is not that interesting architecturally beyond the front façade and cupola. It has 26,000 square feet of useable space, including the noisy “Blue Room” on the second level, but the overall layout is impractical for most purposes.

Before the town starts spending millions of dollars to stabilize and upgrade the hall, it should investigate replacing it with a facility that meets modern standards and expectations. Some of the original elements could be used to retain a sense of its history. Brindisi said it would cost $5 million to tear down the structure and $48 million to construct a new one. But there’s no guarantee that the renovation work won’t add up to that much over time and produce a less satisfying result.

Either way, there’s no doubt that having a medium-size performance venue downtown is crucial. Memorial Hall can seat 1,448 people. That’s big enough to attract name performers who can’t fill Boston’s Orpheum theater or the MGM Music Hall but have enough fans willing to pay $100 or more to hear their music in an intimate setting. Musicians such as Neko Case, Aimee Mann, or Cat Power are a perfect fit. It wouldn’t hurt the nearby Spire Center, either. The downtown jewel is too small for acts of that stature.

Over the years, Memorial Hall has hosted everything from weddings to costume parties to graduations to dance competitions to pickleball and community programs. And don’t forget its original purpose: To provide a place to honor the town’s veterans. They deserve something better.

Letting all that go away is inconceivable.

Under Goldberg’s oversight, the venue, despite its sorry state, has been successful. Before the Covid pandemic, there were fewer shows, and attendance averaged between 500 and 600 people. Now, it hosts about 120 shows a year, he said, with an average crowd of 1,100.

The “majority” of attendees come from out of town, Goldberg said. “They’re going to restaurants, and a lot of them are traveling, so they’re using our hotels. Try to get a hotel room on a show night. The next morning, they get breakfast.”

But there is a caveat. Some of the hall’s revenue comes from the popular Cage Titans, billed as “New England’s #1 Combat Sports Promotion.” Memorial Hall has hosted more than 70 of the events. Eight years ago, a 26-year-old fighter died after being knocked out during a bout in Plymouth. Fans may savor the sanctioned violence, but the bookings smack of desperation. And from what local restaurant owners have told me, the spectacles don’t do much to boost business.

Goldberg, of course, can’t say that. He called Cage Titans “a very lucrative money maker for the town.”

Blood money, perhaps.

Still, it’s clear that he is all-in on Memorial Hall.

“It is the heart of the town,” he said. “My kids graduated here. I’ve been invested in this building since 2008.”

“The other thing, and it’s going to sound corny, but at the end of show when you’re standing at the front door and you see people with a smile on their face…life’s hard, but for a moment you just brought some happiness that they want to come back and experience again.”

This October will mark the 50th anniversary of the most famous shows to take place at the hall: The two-night launch of Bob Dylan’s legendary Rolling Thunder Revue. If you’ve seen Martin Scorsese’s 2018 documentary chronicling that tour, you might have noticed that Memorial Hall looked the same back then. In this case, that’s not a positive.

Brindisi’s two-year countdown clock shouldn’t be dismissed. Time is running out, costs are always rising, and studies can become death knells. As Dylan sang, “A hard rain’s a-gonna fall.”

Mark Pothier can be reached at mark@plymouthindependent.org.