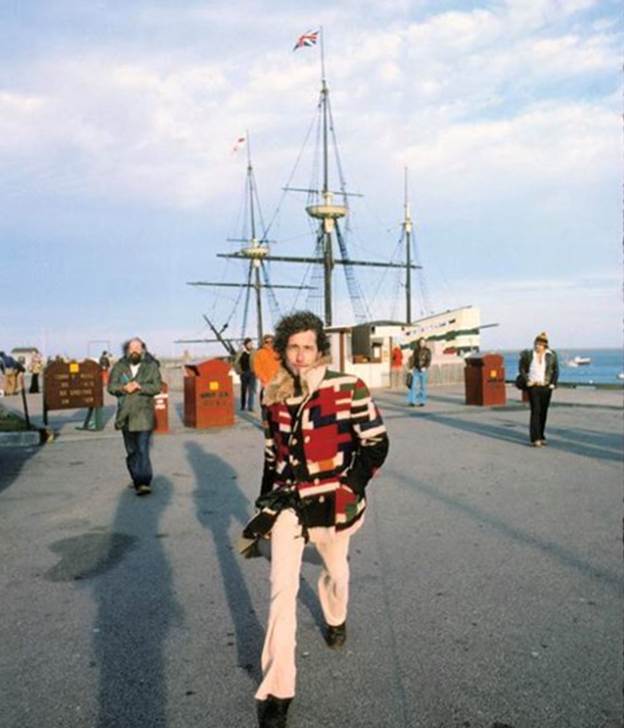

I’m in Pilgrim Memorial State Park, standing near a landmark. Not Plymouth Rock or the Mayflower II, but a cluster of trees where Bob Dylan posed for the cover of his “Desire” album in late October 1975. The shoot, by famed photographer Ken Regan, took place when Dylan was here to launch the Rolling Thunder Revue, a monumental event in the town’s history whose significance deserves more appreciation.

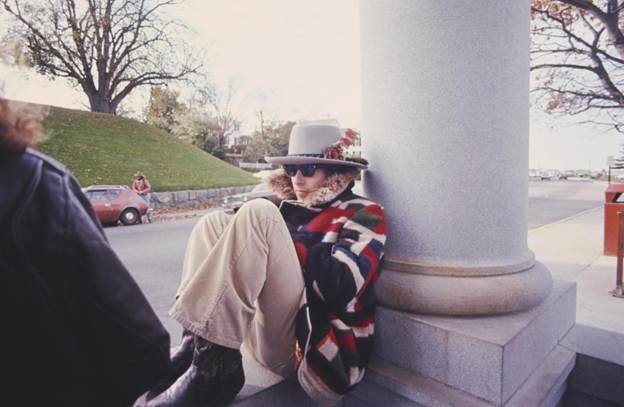

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and the playwright and actor Sam Shepard were on the waterfront that day, too. The surreal scene was captured by Regan – Dylan on the Mayflower, sprinting along the wooden planks of State Pier, standing in a small boat with an entourage, and sitting inside the Rock’s portico, legs tucked, dressed in a colorful Peruvian coat given to him by actor Dennis Hopper.

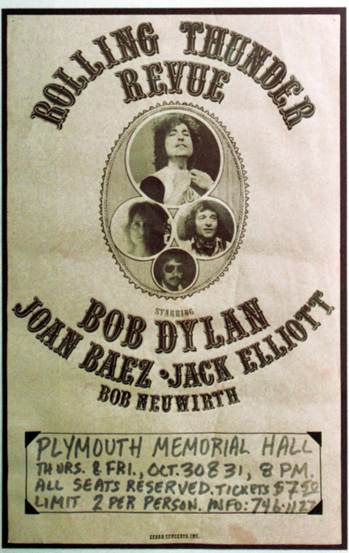

Fifty years later, the trees remain, as does Memorial Hall, where the opening Rolling Thunder shows took place on Oct. 30 and 31. The promoters paid $250 to rent the spartan space. Tickets cost $7.50.

Dylan, at 84, continues to perform today, but Plymouth is a dramatically different town. And as the years have piled up, memories of those 1975 performances have become muddied with myth.

The concerts were pop-up events of their time. In the pre-Internet era, word-of-mouth was the equivalent of “going viral.” That’s how most people found out Dylan was coming to Plymouth.

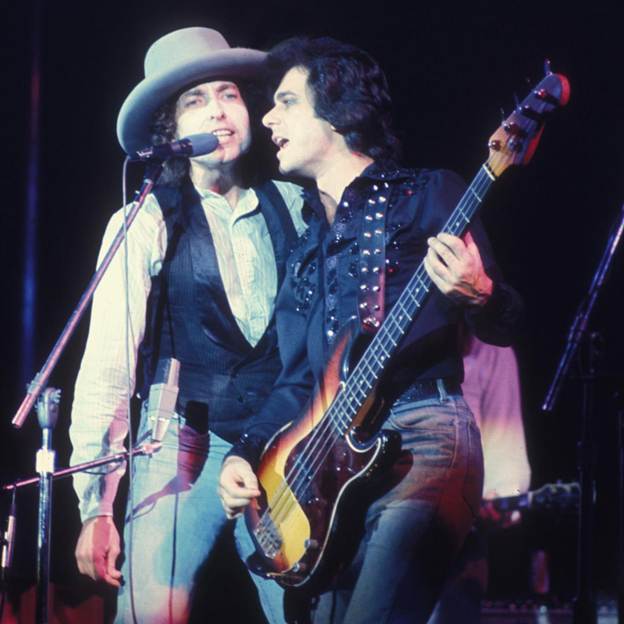

The touring ensemble – a circus-like collection of performers and artists – came together in a pseudo-organic frenzy. It included Joan Baez, David Bowie guitarist Mick Ronson, Bob Neuwirth, T-Bone Burnett, Steven Soles, David Mansfield, Scarlet Rivera, Rob Stoner, Howie Wyeth, Luther Rix, Ronee Blakley, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Roger McGuinn. Along the way, there were guest appearances by Joni Mitchell, Robbie Roberston, Rick Danko, Roberta Flack, Gordon Lightfoot, and others. (Planned poetry readings by Ginsberg were dropped to trim the show’s length.)

My fascination with Dylan began when, at nine years old, I heard “Like a Rolling Stone” exploding from a car radio in the 1960s. In 1974, I saw him reunited with The Band at the old Boston Garden. That tour was an arena spectacle – the first time he had gone on the road in eight years. It’s chronicled on the album “Before the Flood.”

So when the Rolling Thunder Revue materialized in the fall of 1975 with 30 shows booked at small venues, it took everyone by surprise. (He’s back already?) Larry Sloman wrote in Rolling Stone that the idea was to “play for the people.”

“The atmosphere in small halls is more conducive to what we do,” Dylan said.

In his 2002 book, “On the Road with Bob Dylan,” Sloman offered his take on why Plymouth was chosen as the site of Rolling Thunder’s coming out party.

“There was a certain humility and reverence mixed with a pinch of arrogance in choosing this place to kick off the tour. This was one of the first settlements of the New World after all…For Dylan and company, it was the perfect place to make their new beginning, to kick off their caravan, to bring to the people in as direct and unimpeded a manner as possible the messages that sustained and fed our culture through the ’60s and which power the sounds of the ’70s. It was to be Plymouth Rock for the bicentennial. The symbolic significance aside, a town with a population under twenty thousand ain’t a bad place to break in the act before you hit Boston and Montreal.

Down the road from Walgreens is the Plymouth Memorial Auditorium. An old imposing building, lots of nice woodwork, seating about 1,800 at most, including the sea of folding chairs that have been set up on the basketball court floor. The place had been rented the previous week by Barry Imhoff’s advance men, Jerry Seltzer and Jacob Van Cleef…At first, they told the Plymouth authorities it was to be a Joan Baez concert, but then word was leaked on some local radio stations and Seltzer and Van Cleef started distributing handbills, which featured ornate Wild West show logos and photos of Dylan, Neuwirth, Elliot, and Baez under the Rolling Thunder Revue banner. And the tickets started getting snapped up in this predominantly working-class town, even at $7.50 a shot. So as we pull up to the auditorium a good hour before showtime the handwritten sign on the red brick edifice spells it out: BAEZ-DYLAN CONCERTS BOTH PERFORMANCES SOLD OUT.”

The entourage next traveled to UMass Dartmouth and then to a dank gymnasium at Lowell Tech (now the University of Lowell) on Nov. 2, 1975, a show I attended. A friend of mine who was a student at the school gifted me a ticket, knowing that failure to do so would have resulted in repercussions.

Over the decades, those three-plus hours have congealed into an overarching uber memory. I remember Dylan, his face painted white, being locked in. He sang with a close-up ferocity far removed from the distanced rock star figure who took the stage a year before. The tour was met with unbridled acclaim.

In his book “Behind the Shades,” biographer Clinton Heylin wrote: “The Rolling Thunder Revue shows remain some of the finest music Dylan ever made with a live band. Gone was the traditionalism of The Band. Instead, he found a whole set of textures rarely found in rock.”

I spent hours thinking about how to mark the 50th anniversary of Rolling Thunder in Plymouth. It’s been written about in books, dissected on podcasts. It was the subject of a 2019 Martin Scorsese documentary featuring restored footage from the Plymouth and Lowell performances, as well as scenes of downtown Plymouth and Plymouth-Carver High School. In one, a man handing out fliers on Main Street asks two teens: “What were you going to do on Halloween night?”

“Get a buzz on,” one of them says with a smile. “Nothing else to do.”

In another sequence, someone asks offscreen, “Why is he coming here?”

People who managed to snag tickets are now in their late 60s or older. Some recount vivid tales of the Rolling Thunder incursion; others remember it through the gauze of time. (See the accompanying story to read some of their recollections.)

Considering that Dylan rarely does interviews, and didn’t even attend the 2016 ceremony to receive a Nobel Prize in literature, the chances of him dishing to me about his days here were less likely than Plymouth electing a mayor anytime soon. (Bob, you can still email me at your earliest convenience.) I needed a backup plan for this 50th year remembrance.

It turned out that Plan B was Grade A – Stoner, who played bass and sang on the tour, graciously agreed to talk. Shepard wrote in his 1977 “Rolling Thunder Logbook” that he was “the brains behind the operation, grafting harmonies onto Dylan like a Siamese twin.”

Beyond his onstage duties, Stoner was weighted with the herculean task of molding the ragtag cluster of musicians into a cohesive unit. He did it without much direction – home or otherwise – from Dylan. As you’ll read, the effort almost qualified him for his own Nobel.

Stoner met Dylan in 1971 and jammed with him in Kris Kristofferson’s room at the Sunset Marquis hotel in West Hollywood. In retrospect, he suspects it was part of a vetting process.

But Stoner didn’t record with him until July 1975, when he played on the New York sessions for “Desire,” an album that routinely lands near the top of Dylan’s 60-plus-year discography. It held the number one spot on the Billboard chart for five weeks.

(This conversation has been edited for clarity and length. To hear surprisingly good-quality recordings from the Oct. 30, 1975, performance at Memorial Hall, go here.)

A lot of time passed from when you met Dylan to the “Desire” sessions. Were you surprised that he wanted you on the album?

He had stayed in touch with me over the years and eventually, just as I assumed, The Band went out on their own and didn’t want to work with him anymore, so he needed a new group. I was in his Rolodex and he gave me a try.

And how did mounting another tour come up so soon after the massive one in ‘74?

He wanted to scale back, to do something that was more nuanced and had more dynamics to it. When we did “Desire” that became the direction he wanted to go in. I could hear as we were recording the album that he liked that there were acoustic instruments. That was where he was comfortable. It was one marathon session in the end.

What happened after that?

Dylan’s such a weird guy. I think we shook hands – “thanks, nice job.” I never knew if I was going to hear from him again. He never said, “I’m going to call you. We’ll do some gigs together.” But I was used to that as a freelance musician. Most things are a one-off. But I was pleasantly surprised about a month and a half later when his office got in touch with me to go to Chicago and do this live thing. He wanted to see if what we had accomplished in the studio could be replicated live. That was our live audition, on television, no rehearsal. In fact, one of the songs I only knew from the radio – “Simple Twist of Fate.” I had no idea whether I passed the audition but heard from him a few weeks later when he was sort of planning the Rolling Thunder Review. It was already October.

I assume you couldn’t just ask, “Am I in the band or what?”

Exactly. If you were too forward with him, you’d be out, or he’d give you some kind of enigmatic answer, some kind of nonsense to shut you down.

Did he ever say, “I want you to put a touring band together and I want it to be eight or 10 people on stage?”

No, it evolved, and from what I could see, kind of chaotically. It seemed kind of random [as to] who was showing up [to play], although I found out later there was a method to it.

He asked Patti Smith and Bruce Springsteen to be part of the revue.

Patti was invited, but she didn’t want to go without her band. Springsteen gave the same story, too.

His star was ascending with “Born to Run,” which came out that August.

It wouldn’t have made sense for him. He had gigs booked and so did Patti. Dylan expects you to drop everything. You can’t make plans. Fortunately, I was able to get out of all the gigs I had lined up because they weren’t that important. But if you have a tour booked for your solo career, you can’t just flake out on the promoters and the manager. And this thing seemed flaky at the outset. The way it was presented was “we’re just going to get a bunch of people who travel in a caravan. People will show up along the way and play.” I listened to this and thought: These people are delusional. It’s unprofessional. It’s going to be a hippie-dippy mess, man. When the rehearsals started, people were coming in and out. Nothing was organized.

You became the band leader by default?

Well, somebody had to crack the whip.

Maybe he noticed how you took charge of the “Desire” sessions.

I’m sure that was part of it – he knew I could filter out the [extraneous] stuff.

Leading up to the Plymouth shows you rehearsed at the Sea Crest hotel in Falmouth.

Yeah, but first we had spent a week rehearsing in Manhattan. Thank God for Jacques Levy (an influential theater director, songwriter, and clinical psychologist). He knew how to stage a show and organize exits and entrances and blocking – all the stuff you’ve got to have so people aren’t wandering on and off the stage. You don’t want to have a static bunch of musicians up there all the time. People have to be entering and exiting for their exact song. Our goal was to have it organized like a stage production.

Of course, at the center of it, you’re dealing with this mercurial, inscrutable guy who is known to not be organized and changes things on a whim. He’s not the ideal guy you want as the ultimate arbiter of what’s going to happen.

It still had a feeling of being impromptu.

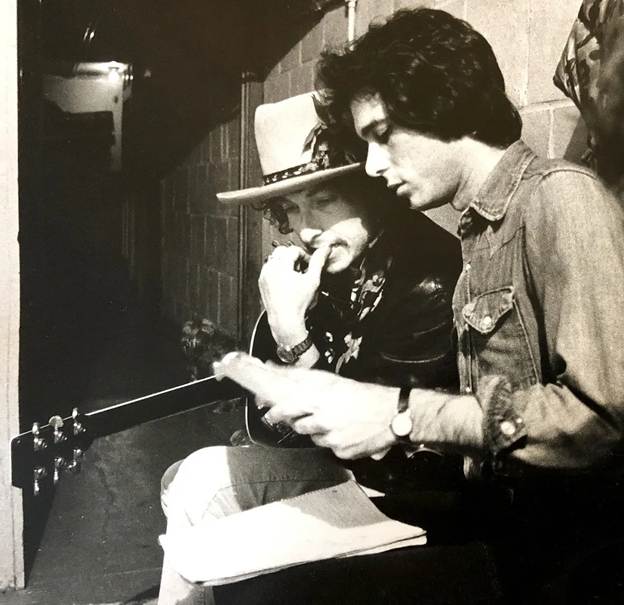

It intentionally looked loose. But I have lighting and sound cue sheets for the entire show for every song. Any number of other people were on board were qualified to be the musical director. I mean, we had Mick Ronson from Bowie’s tours and T-Bone. But nobody stepped up. Maybe because it seemed so daunting. I went back with Dylan the longest of any of those people having already done “Desire.” I just stepped into the breach.

I would go back to my room and listen to tapes of the rehearsal or the gig, take copious notes, and come in the next day to implement changes based on what I thought needed improvement. Most executives like to delegate so they don’t have to talk to too many people. Dylan is an example of that. He didn’t want people to come up to him and ask him questions. He would say, “Talk to Rob.”

Did that make you invaluable to him?

I was the Bob Whisperer. I was in the right place at the right time, with the ability to accomplish what he was looking for from an executive assistant. He was looking for a surrogate who could rehearse the band and sing his songs as a stand-in vocalist. It was just like in the movies. Robert Redford didn’t show up until they got the camera angles right. Then he came out of his trailer. It was just like that.

Take me back to opening night in Plymouth.

I was very relieved that it was a low-key little auditorium with folding wooden chairs. It was not in a big media city on a big, bright stage where all the imperfections that had yet to be ironed out would be glaringly visible. It was the shakedown cruise.

Nonetheless, those first couple shows were remarkable.

Well, the chemistry was there, but the loose ends were driving me crazy. There were a lot of songs that didn’t have intros. You’ve got to have an intro and an outro. A song has to be organized. You have to vary things. Otherwise, the songs all sound the same. That’s where I came to rely on [David] Mansfield and Ronson, to put in those extra colors. I didn’t want [the performers] looking like a bunch of stupid hippies up there roaming around. I was scrambling to try and tighten up the tunes.

Did Dylan know you were up at night obsessing over how to make the show better? Did he say anything?

Express pleasure or displeasure? Dylan? Never. He never said, “I don’t know what I’d do without you.” You know, the kind of things a normal person would say. But that was standard operating procedure. I guess everybody’s got their own executive style. Dylan was never one to sing praise.

When was the last time you spoke with him?

Once in a while he asks me to go into the studio and shape up some tapes for the bootleg series. It’s perfunctory. It was a business relationship and business relationships come and go. Our thing had run its course.

Realizing that it was 50 years ago, do you have any memories of what you did in Plymouth that October beyond the concerts?

My waking hours during the early part of the tour were totally consumed with trying not to fail on stage. Everybody else seemed to out having fun, carousing. I felt tremendous pressure to get this sloppy folk music to sound right. But I did get paid double for my extra effort.

You also harmonized with Dylan on stage, which couldn’t have been easy given his penchant for changing phrasing and arrangements without warning.

You’ve probably noticed that on his records and with most of the gigs with The Band there are very few backup vocals. That’s because his singing is so idiosyncratic. He never sings anything the same way twice. You’ve got to watch his face muscles, watch his mouth to anticipate what curve ball he’s going to throw next.

Was that anxiety inducing?

It was a challenge. And I recognize it from other people I’ve worked with who do that – it’s sort of a power trip. They do it to remind you who’s boss.

I’m usually not a big anniversary person, but the Rolling Thunder Revue’s place in musical history is undisputable.

The guy’s had a forever career, and that part of it really resonates with people. At the time, we were in the eye of the hurricane. You have no idea. I’m very happy with the fact that it’s so well regarded.

Mark Pothier can be reached at mark@plymouthindependent.org.