The Select Board Tuesday accepted a consulting firm’s report on how Plymouth could use 1,600 acres around the former Pilgrim nuclear power station in Manomet owned by Holtec International, the company that is decommissioning the plant.

That is, if Holtec decides to sell the property and the town can afford to buy it. The cost is estimated at between $50 million and $90 million.

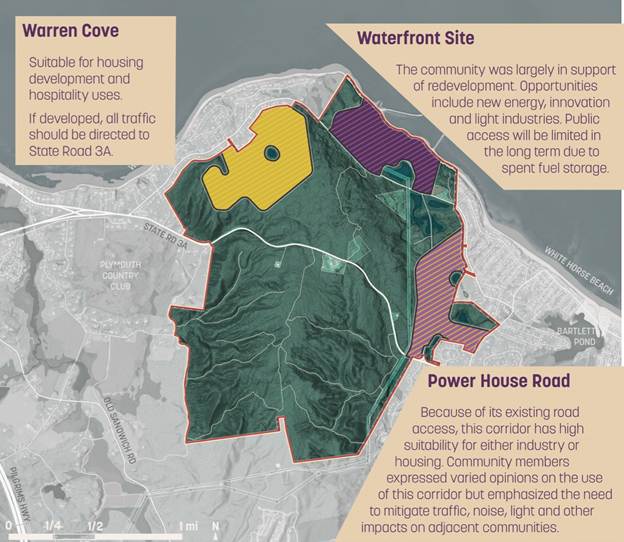

The report from Sasaki Associates – detailed during a lengthy presentation at Tuesday’s Select Board meeting – outlines options the town might take if it is able to acquire the land or needs to negotiate a deal with whoever buys the property. It includes proposals for housing, conservation, and light industrial use on different parts of the property that Sasaki estimated could bring in $1.2 million a year in revenue to the town andcreate 860 to 1620 jobs.

The town has the right of first refusal on 1,531 acres, but that is not the case with another 144 acres of waterfront property owned by Holtec that includes the former power plant itself, as well as the problematic spent fuel casks.

Holtec has not indicated whether it intends to sell the larger parcel, but if it does and the town is not able to meet the asking price, officials could still negotiate with the company or developers to leave some of the land in conservation in exchange for rezoning to allow development on other parts of it.

Under the proposal, most of the site would be kept as open space, with a trail system for hikers and mountain bikers. But Sasaki said the town could opt to allow 110-210 housing units and 110-190 hotel rooms in the northwestern part of the land, near Warren Cove, with an access road to be built from Route 3A.

The idea of building housing, however, was not popular with any of the five Select Board members.

“I do have concerns about housing development on the site,” said Select Board Chair Kevin Canty. “I’d like to see little to no residential.”

Along Powerhouse Road, the consultants proposed light industrial use and small pockets of retail space.

Sasaki said the town could rezone some of the property to attract innovative industries. Most of it is now zoned rural residential. Lee Hartmann, the town’s director of planning and development, said in an email Wednesday that the designation means a developer could build single-family homes with lot sizes of about three acres apiece.

Sasaki cited the appeal of being close to the former power plant’s switchyard and high-voltage line. On the other hand, the lack of easy access to Route 3 is a barrier to industrial development, it said.

The company recommended forming an innovation district like the Devens Regional Enterprise Zone, creating a partnership between the town and state to funnel new tenants to the area.

To attract industrial development, it said, the town would have to consider infrastructure upgrades, such as supplying water to the area. It would have to acquire well sites and designate wellhead protection zones. It would also have to identify and invest in wastewater treatment systems by extending lines from the Plymouth municipal system, building a private onsite wastewater treatment plant, or establishing a new public sewer district.

The report said the town should consider whether Powerhouse Road should be transferred from Holtec to town jurisdiction. It also recommended widening Route 3A in that area.

In addition, the consultants recommended planning for a maritime public safety facility and a police and fire substation.

The infrastructure requirements seemed to surprise, or at least concern, Select Board member Deb Iaquinto.

“The infrastructure demands kind of took my breath away,” she said.

Iaquinto, who – like her fellow board members and many residents – took part in the months-long process leading up to the report, favors leaving most of the land as open space.

“It’ll be a hard sell for me to develop even 10 percent of that land,” said board member Dick Quintal. “My vote would be [a small modular nuclear reactor] and every piece of that property would be put into conservation. I say leave it alone.”

Hartmann said conservation was a popular sentiment with most of the people who provided input.

“What we heard from the community is we want to protect as much of this land as possible,” he said. Hartmann, along with Sasaki, led the effort to solicit community input that included polling residents and two in-person forums attended by dozens of people.

“There’s a willingness to have some development if that results in protecting the majority of this land,” he said.

Sasaki advised setting up a governance structure to establish and maintain the conservation acreage to purchase the property. The town could work with other entities to acquire and maintain the land. For example, it said, the Wildlands Trust could work with the town to hold land in conservation and have other organizations, such as the Pine Hills Area Trail System and the New England Mountain Bike Association, maintain a trail system.

The consultants said the town would need to come up with money to pay for such conservation. It suggested payments in lieu of taxes from Holtec or interested developers, as well as state and federal funding and nonprofit partners. The town could also leverage agreements to allow more development in more densely populated parts of town in exchange for a developer agreeing to put the Holtec land in conservation.

Sasaki also recommended establishing a network of recreation and ecotourism destinations on the land that would include lodging and restaurants. It calculated that the site could attract 144,000 visitors a year, generating $8 million to $12 million from tourism annually.

If the town was able to also buy the 144-acre waterfront site where the former plant sits, several options were offered. They included connecting to potential future offshore wind developments, small modular nuclear reactors, utility-scale battery energy storage systems, and rooftop solar to power adjacent light industry or to supply the town with cheaper electricity. Sasaki said the town could negotiate payments in lieu of taxes with Holtec or a subsequent owner of the property.

For example, the town could negotiate a permanent buffer zone in exchange for allowing development on the 144-acre site.

The idea of building small nuclear reactors, or SMRs, on the smaller site to help supply electricity to Plymouth has been a hot topic. But Canty said he opposes them unless the existing nuclear waste is removed.

“There’s been a lot of talk about SMRs or further nuclear reactors,” Canty said. “To me, we need to get rid of the dry cask storage before we even have a conversation about that, because we haven’t cleaned up from the last party and shouldn’t be starting to talk about hosting another one.”

The purpose of the report is to provide a roadmap for town officials over the next few years as they negotiate to purchase the land or impose conditions on its development. There is no immediate next step.

Fred Thys can be reached at fred@plymouthindependent.org.